ASPECTS OF EARLY EGYPT

EDITED BY

JEFFREY SPENCER

BRTTISHMUSEUMPRESS

�The Relative Chronology of the Naqada Culturet

Problemsand Possibilities

Stan Hendrickx

l.Introduction.

Terminologyregardingthe relativechronologicalperiodswithin the predynasticand early dynastic

culture of Egypt is nowadaysfrequentlyusedin a mannersuggestingcompletereliability. Nevertheless, severalfundamentalproblemsconcerningthe relativechronologyof the Naqadaculture still

by severalauthorsthatno generallyacceptedterminologyexistsfor

exist.It hasalreadybeenstressed

Egypt's late prehistoryandearlyhistory (e.g.Mortensen1991:fig. 1; Tutundzic1992).For instance,

(Scharff1931: 16-30;Kantor1965;Baumgartel

(Petrie1920:46-50),Protodynastic

thetermsSemainean

1970a),NaqadaItr (Kaiser 1957;1990:Abb. 1) or TerminalPredynastic(Hassan1988)canbe used,

the

andareactuallyused,for moreor lessthesameperiod.Besidestraditionandpersonalpreferences,

main reasonfor this confusionseemsto be that the termsarein mostcasesill-defined,both archaeologically as well aschronologically.Sincethe relativechronologyof theNaqadaculturehasnot been

andsincemeanwhilethe availableinformadealtwith in a systematicway duringthe lastfew decades,

to re-examinethe subject.

it seemsabsolutelynecessary

tion hasincreasedconsiderably,

2. SequenceDating.

The original study goesback to the early yearsof the century whenW.M.F.Petrie worked out his

SequenceDating (Petrie1899;Petrie& Mace l90l: 4-12; Petrie 1920:34), the first attemptat what

is now known as seriation.The SequenceDating is basedon the gravegoodsfrom the cemeteries

at Naqada,Ballas(Petrie& Quibell 1896)and DiospolisParva

excavatedby Petrieandhis assistants

'predynastic'pottery,

(Petrie& Mace 1901).As a fust step,the potterywas uuranged

in a corpusof

consistingof nine classesof potteryandover 700types(Petrie1921,seealsobelow,pp.44-46).Next"

all objectsfrom eachgravewerenotedon a slip of card.Finally,thecardswerearrangedin a relative

of types.In this stageof thework, Petrieusedonly nine

chronologicalorderbasedon theresemblance

graves

five

intact

or moredifferentpotterytypes,out of over four thouhundredrelatively

containing

sandexcavatedgraves.The chronologicalorderwasdefinedby two mainprinciples.First, an earlier

and a later phasewere distinguishedthroughthe observationthat the classesof White Cross-lined

pottery on one hand,and Decoratedand Wavy Handledpottery on the other hand,neveror almost

neveroccured together.Secondly,it wasacceptedthattherehadbeena degradationof the form of the

Wavy Handledtypes,going from globularto cylindrical shapes.When all gravecardshad beenar.-gia in order,pltrie dividedthe cardsinto fifty equalgroupi, eachof themconsistingof 18 graves,

numberingthem as Sequence

Datesfrom thirty to eighty.By choosingto startat SD 30 he left space

for earliercultures,which he thoughtwere still to be discovered.Finally the fifty SD's weredivided

culturallyandchronologicallydifferent.

into threegroupswhich he consideredto be archaeologically,

'cultures'

were namedAmratian (SD 30-37),Gerzean(SD 38-60)and Semainean(SD 60-75),

The

after someimportantpredynasticcemeterysites.

'protodynastic'potThe Sequence

Dateswerecontinuedwith a secondtypologicalcorpus,for the

atTiukhan

tery (Petrie1953).This is almostexclusivelybasedon materialfrom theextensivecemeteries

(Petrie,Wainwright& Gardiner1913,Petrie 1914).This time the numberof typesreached885 (see

partly overThe 'protodynastic'corpus

below,pp.a6-a7)andno classesof potteryweredistinguished.

'predynastic'

Datesfor

corpus,asa resultof which the Sequence

lapswith themostrecenttypesof the

the 'protodynastic'corpusstartfrom SD 76 andcontinueto SD 86,which shouldmark the beginning

of theThird Dynasty.However,theSD's 83-86remainedalmostcompletelytheoreticalbecauseof the

Datesis not carried

lack of SecondDynastymaterial.Thedistinctionbetweenthe individualSequence

36

�Date is

out in the samemanneras for the predynasticcorpus,but the transitionto a new Sequence

HanWavy

the

bur.d on typologicalbreakswhich Petriedefinedmainly throughthe developmentof

Datingwith the historicallydatedpotterytypesand

dt.d ,yp"r. Finally,PetrieconnectedtheSequence

atAbydos(Petrie,Wainwright& Gardiner

tombs

earliest

dynasties

the

royal

of

the

otherobjectsfrom

1913:3).

oneof the major intellectual

Datescertainlyrepresents

Althoughthe developmentof theSequence

shortcuts

(cf.

methodological

anumberof

predynastic

1963),

Kendall

of

Egypt

study

the

in

achievements

(1913),

Scharff

whomLegge

andpossibleerrorswereafterwardspointedoutby severalauthors,among

(1955:2, 1970a:4-5)and Kaiser(1956b)arethe mostim(l9M), Baumgartel

Ogi6:7I4), Kantor

problems

methodological

severalpointsmay be noted.

Among the

Dortant.

It is obviousthatPetriemakesno cleardistinctionbetweentypologyandchronology.He postulates

theevolutionof theWavy Handledclasswithout sufficientevidencefor theearlierstagesof its evolution(Kaiser1956b:93-5).Also,thecriteriausedfor thedefinitionof thepotteryclasses(Petrie1921)

The basiccriterionmay be eitherthe fabric (Roughclass),the methodof firing

areheterogeneous.

and/orfinishing (Black-TopandPolishedRed),the decoration(White CrossLined and Decorated),

theshape(Fancy),a morphologicaldetail(WavyHandled)or the relativechronology(Late).This last

classcausesa specialproblembecauseof the lack of consistencyin potteryfabric (cf. Patch 1991:

l7l). Furtherrnore,the definition of the individual typeswithin theseclassesis not bound by strict

rules(cf. Petriel92l: S).Also, thetypesarenot distinguishedin the sameway for eachof the pottery

All these factorswill causeproblemsfor any type of seriation,includingthe onedevisedby

classes.

petrie.Whensubsequent

useis madeof this kind of rypologicalcorpusfor typing objectsin the grave

of excavationsnot carriedoutby Petriehimself,it is only to beexpectedthaterrorsarebound

registers

to arise.

Petrie

Cal BC

PetrieSD's I numberSD

_s-"ssr,sgr_-ir-lgkLfq__igq__-+pJ6_-i-tt----ig{g---,

2----+-zs----;1t49-Qgp*!----j-1€t1390---+-3lL---+iqf

Amratian!:soo:oso!zso izr-tt

irs.zr

it

(1). After Hassan(1988):138.

Tab. 1. Absolute chronologicalimplicationsof Petrie's SequenceDates.

As alreadystated,the systemwas developedusing only nine hundredgravescontainingfive or

morepotteryfypes.Sinceit is now obviousthat the averagenumberof objectsin a graveincreased

throughtime (cf. Seidlmayer1988),it is generallyacceptedthat this causesthe earlierperiodsto be

under-represented

by Petrie(e.g.Petrie1920:4;Kaiser 1956b:92). However,if we testthis ideawith

thecurrentlyacceptedabsolutechronology,a ratherpuzzlingimageappears(table1).The importance

of thefinal phaseof thepredynasticperiod,asdefinedby Petrie,seemsnot over-represented,

although

tt remainsa fact that the earliestphaseis under-represented.

probably

This is most

the result of the

numericallydominatingrole of theMain Cemeteryat NaqadawhenPetriedevelopedhis theSequence

Dates.Indeed,at this cemeterythenumberof gravesbelongingto the NaqadaIII periodis restricted

(cf.Paynet992: frg.l-Z).

The SD's for the 'predynastic'and the 'protodynastic'corpuswerenot definedin the s:rmeway.

_.

Ihrs implies of coursethat their eventualchronologicalvalue cannotbe compared.Also, the

protodynastic

SD's weredefinedby meansof typologicaldifferences,which werea priori acceptedto

navechronologicalvalue.Furthermore,Petrietreatscemeteriesfrom differentsitesas an entity. He

acceptsthe cultural uniformity of the predynasticculrureas guaranteed,leavingno place for local

variation.This is characteristicof the time when Petriewas working; far moreattentionwas paid to

culruraldiffrrsionthanto local

srowthandevolution.

5t

�Finally, the definition of the original SequenceDateswasmadein a mannerto minimize the chronological dispersionof eachtypeof pottery.This resultsin a compromisebetweenthecompetingclaims

of all pottery types for closerproximity. This perfectbalance,however,is purely artificial, since,

Datesfor a numberof typeswill

whenevernew gravesareaddedto the system,therangeof Sequence

Dating becomespurely hypothetiby the Sequence

haveto be expandedandthe accuracysuggested

cal. Also, it is not at all clear in what mannerPetrieaddednew typesto the alreadyexistingcorpus.

types(e.g.Wavy Handled)in the company

Probablynew typesweredatedaccordingto characteristic

of which they werefoundandno longeraccordingto gravegloups(Mortensen1991:16).Of couise,

the archaeological

when addingnew datato the system,the original point that eachSD represented

was

originally

basedon an

materialfrom 18 graveswas also lost. Obviously,the fact that eachSD

a similar periodof time. This was

equalnumberof gravesneverimplied that every SD represented

of the system,since

(Petrie

an

inconvenience

remained

4)

and

always

1920:

himself

realisedby Petrie

one automaticallytendsto considerthe SD's as chronologicalunits.

However,the moststrikingomissionof Petrie'sway of workingremainsthefact that he nevertook

the horizontaldistributionof the gravesinto consideration.This despitethe fact that he noticed,for

instance,that noneof the cemeteriesfrom DiospolisParvacoveredthe whole rangeof the Sequence

'early' and 'late' cemeteriescould be distinguished(PetrieaadMace

Datesbut that,on the contrary,

lgOI:3I-2). Strangelyenough,Petriedoesnot mentionspatialdistributionwithin the cemeteriesof

Naqada,Ballasor DiospolisParva,althoughit is hardly imaginablethat he did not noticeanythingat

all. On the occasionof later excavationsby former assistantsof Petrie, the existenceof groupsof

chronologicallyrelatedgraves,andthereforethe differencesin the spatialdistributionof objects,was

noticedseveraltimesat differentsites(e.gRandall-MclverandMace 1902:3;AyrtonandLoat 1911:

1928:50-1)but no attemptsweremadeto usethese

2; Peet1914:18;BruntonandCaton-Thompson

purposes.

observationsfor chronological

3. Snfen chronologr

Although SequenceDating was rightly criticised,the generalprinciplesof the developmentof the

Naqadaculfilre, as establishedby Petrie,were never fundamentallycontradicted,neither are they

Datingcannotbe maintained,

it haslong beenobviousthatthe originalSequence

today.Nevertheless,

sinceit givesa misleadingideaof greataccuracy,while in realitythe systemwill becomeincreasingly

Dating is nowadaysgenerallyreplaced

impreciseasnew dataare incorporated.Therefore,Sequence

by W. Kaiser'sSrufenchronology(Kaiser 1957).Unfornrnately,the study of Kaiser was only pubby elevenplates,andthis already

lishedin anabridgedversionasan articleof ninepagesaccompanied

publication,

Kaiserwasunableto include

38 yearsago.Becauseof the limitationsof spacewithin the

detailson his analyticalmethod.RecentlyKaisermentionedin an article the extensionof his Snfen

chronologyinto the First Dynasty(Kaiser 1990:Abb. 1, seealsop. 42),but the mannerin which this

was donestill remainsunpublished.

In his original study,Kaiserstartsfrom the horizontaldistributionof potteryclassesand typesof

objectswithin the cemetery1400-1500at Armant (Mond and Myers 1937).Althoughthis cemetery

was publishedto a very high standardfor the time, the identificationof the objectscannotbe controlin

led, sincetheoriginalobjectsareno longeravailableandonly typeswhich werenot yet represented

of Blackthe corpusweredrawn.Threespatialzonesweredistinguishedby the relativepercentages

Topped,RoughandLateWares,eachof themdominatingonezone.Thesezonesareconsideredto be

chronologicalstages,which canberegardedasthethreemainstagesof thedevelopmentof theNaqada

calledStufen,wererecognisedaccordingto the

culture.Within thesethreeperiods,elevensubperiods,

clusteringof typesof objects,chiefly pottery.ThusthedistinctionsbetweentheindividualSufen,and

thereforealsobetweenthe threemain periods,aremadeup primarily on the basisof objecttype and

containsonly 149gravesandmorethan

notby therepresentation

of wares.SincetheAnrumtcemetery

half of the potterytypesoccurredonly once,the groupingof limited numbersof relatedtypeswuls

unavoidable(Kaiser1957:77,n.67),althoughthis is not freefrom risk (seebelow).Of course,this

methodcan be criticisedfrom the methodologicalpoint of view, sinceit more or lesspostulatesthe

38

�chronologicalimplicationsof the spatialdistribution,but this doesnot seemto be a major practical

problemwithin Egyptiancemeteries.

Dating,Kaiser'ssystemhasthe advantageof includingnot only

When comparedto the Sequence

but alsofrom the spatialdistributionof the objects.

the informationfrom the typologicalapparatus,

Furthermore,it doesnot give an impressionof extremeaccuracy,but by defining periods,it escapes

asnew dataare

largely,althoughnot completely,the problemof becomingincreasinglymeaningless

added.

However,this doesnot meanthat thesystemis free from problems.AlthoughKaiserincludeddata

besidestheoneatArmant,essentiallyit remainstruethatdatafrom only

from a numberof cemeteries

a singlecemeteryhasbeenusedfor the descriptionof the NaqadaculturethroughoutUpper Egypt.

Kaiser is well awareof the possibilitiesfor regionaldifferentiation,and has noticed

Nevertheless,

regionalphenomena,at Mahasnafor example(Kaiser 1957:74).The problem causedby using the

cemeteryof Armantbecomesevenmorecomplicatedsincethe earliestphaseof theNaqadacultureis

not presentthere,andalsothe mostrecentphasesarevery sparselydocumentedor absent.Therefore,

thedefrnitionof theSnfen Ia andIb is basedon merehypothesis,althoughexamplesfrom cemeteries

otherthanArmantaregiven.The descriptionof Snfe IIIb, thoughlesshypotheticalthanSnfen Ia and

ln mostcasesit was not possibleto studythe

Ib, is alsobasedon informationfrom othercemeteries.

spatialdevelopmentof thesecemeteriesand thereforeKaiser'sdescriptionof Snfen Ia-b and IIIb

dependslargelyon the theoreticalevolutionofpottery typesasalreadyacceptedby Petrie.

An initial point of debateis whetheror not Kaiser'sdivisionof theNaqadacultureinto threephases

is valid. If so, it shouldbe questionedwhetherthe limits of the threemain periodsof the Naqada

culturearebasedon factswhich are sufficientlyobvious.As far as the distinctionof threeperiodsis

concemed,there seemsto be no problem on frst inspection.Severalcemeteriesbelongingto the

Naqadaculturebearevidencefor the presenceof threegroupsof graves,dominatedrespectivelyby

thepresenceof Black-Topped,RoughandLatepottery.However,thesethreeclassesareidentifiedin

differentmanners(seeabove,pp.44-5),althoughBlack-Toppedstandsprimarily for a Nile Silt fabric,

Nile Silt fabric while Late standsmainly (cf.

mainly Nile Silt A; Roughstandsfor a straw-tempered

below)for a Marl fabric (for all fabrics,cf. Nordstrcim1986).Most of the otherpotteryclassesanda

numberof their individual types can be attributedto one of thesethreefabrics.It would be more

logicalto studythe spatialdistributionofthe threefabricsandnot only ofthe potteryclassesdefined

by Petrie.Kaisernotedthe problem and describesthe relationbetweenthe fabrics and the pottery

classes,but continuesto work by Petrie'spotteryclasses(Kaiser1957:76,note 8).

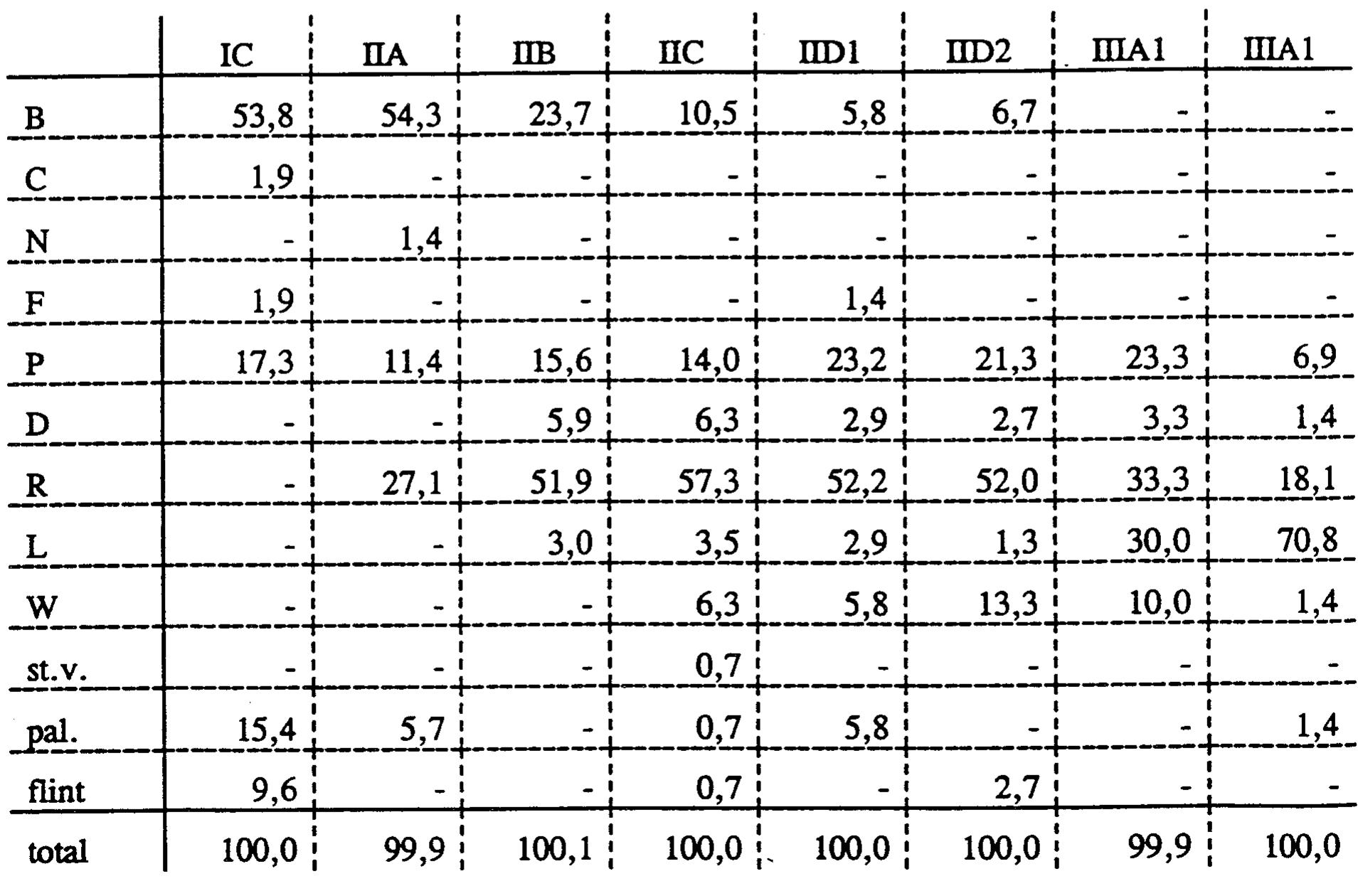

Thetransitionfrom SrzleIto Sufe II at theArmantcemeteryraisescertainquestions(table2a-b,cf.

SrufelshouldbedominatedbyBlackFriedman1981:70-1).AccordingtoKaiser'sgeneralprinciples,

Toppedpottery which is indeedthe case,andStufeII by Roughpottery.This rule, however,fails to

applyfor Sufe IIa, whenBlack-Toppedpotteryremainsdominant.ComparingNile SiltApottery with

straw-tempered

Nile Silt pottery,thedominanceof the secondfabric (52Voo 39 7o)remainslimited

evenfor Sufe nb. The differencesbetweenStufeIIa and Ifb, when the dominantclassof ponery

changesfrom Black-Toppedto Rough,as well asbetweenStufe\b andIIc, with the introductionof

Wavy Handled and a number of new Decoratedtypes,are much more important than the difference

betweenSrufelc and tra (cf. table 2a-b).Anotherpoint of importancein this discussion,is that the

Roughpottery doesnot appearout of the blue at a certainmomentin the evolutionof the Naqada

culture.It is more than obviousfrom settlementexcavationthat the Roughware makesup the large

majorityof potteryfrom thebeginningof theNaqadaculture(e.g.Brunton1937;Hendrickx& Midanr

Reynes1988:8; FriedmanL994),but the Roughware finds its way only slowly to the cemeteries.

Sincethe Roughpottery alreadyexistedat a periodprior to its regularappearance

in graves,its absenceor presenceis not sufficientreasonfor distinguishingtwo main periodsin the Naqadaculture.

However,Kaiser'sdistinctionbetweenStufelandStufeII doesnot dependonly on therepresentation

of thewares.Of greatimportanceis theappearan

ce n StufeIIa of a numberof potterytypes,especially

smallbag-shaped

(R

R

66

a,

R

69 r, R 93 c), whichwerenot yet presentduing Stufe

Roughtypes 65 b,

Ic. Nevertheless,if a distinctionbetweena first and a secondperiod within the developmentof the

Naqadaculture is to be made,it seemsmore logical to draw the line betweenStufena and IIb or

perhapsevenbetweenSrufetrb andtrc.

39

�I

I

I

trA

i tot

ItrAI

IJDZ

IIDI

I

!

1 !

-

t

-

I

I

I

trc

trB

t

I

t :

l

l

r

1 r

---.-1+-

-----!--

t

l

r

l

l

l

| t

J----J.-

l

zri'

8i

9:

l

- 3

- t

---J.----r---:

- r

l

- l

---+-----

l

l

- ---

s

7i

16:

16i

2o1

l

- l

P

R

r

l

- i

9 :

r

- r

' t

- r

t

I

- ,

- r

---+-----i------+---::-

l

l

l

l

4 1

t

I

3 :

+----------

l 0 :

|

|

|

- l

- l

- t

l t

-_---+----+-------+----:+-----+---+-------+--------l

-P-4

flint

l

l

701

l

- r

- r

4 l

._J--_..-+------+r l

r l

.

l l

rl

- !

- 1

total

l

- l

l rl

8 i

4 t

---r----:.-L-----i

l r

- :

1 :

l

I

l

- :

2 t

7si

1351

72

'lab. ?-a.Armant Cemetery140G'1500.Number of objects,after Kaiser 1957.

trA

ITD?

I

54.3|

r

l

t

l

l

1 0 . 5 1 5 . 81

:

+---':J---:-:J----L-+-------4-l

t

- t

l

- l

I

I

IIIAl

l

- 'l

l

l

- l

6,7:

- l

-

- l

- t

l Q t

-----'-;!+------+-.------+--------+------+--------+--------+---------I

t

l

- r

t

- t

l

- r

l

- r

- :

1 . 41

-------+--------+-------+-----+--------+--.----.-+---------+---------

- ll

P

.P

R

---:.i--Z,Li-J1g+--s7Ay-J22i-e'9

j---jlai---lg',-

I

L--

w

-

l

---:+-----:+-----:+---ga+---:'!L-Ea

j----1-q'-0-+--J,4--

I

-

l

I

34

flint

totat

15.4:

9,6i

3

I

-

l

99,9i

- l

I

I

-

l

100,1

i

i 100,0

i- 100,0

: 100,0

-

l

s9,gi

too,o

of potteryclassesfor eachSW, after Kaiser

Tab. 2b. ArmantCemetery1400-1500.Percentage

1957.

40

�The transitionfrom Stufeu.toStufeItr is alsonot without problems.The differencebetweenthem

is madeup by the Late classwhich takesoverfrom theRoughclassasthenumericallymostimportant

group.However,Kaiser'sview of the spatialdistributionof the Roughand Late pottery at Armant

iKuir"r 1957: tf . 15B-C) doesnot takeinto accountthefactthatan importantnumberof theLate types

arein realitymadein the Roughfabric (especiallythetypesbelongingto theL 30 series),althoughhe

is well awareof the problem(Kaiser1957:76,note9). Countingthesewith the Roughclassgivesa

completelydifferentpicture.The Late typesreach50Voof the potterytypesin only one,small,grave

(l5g}), wheretwo out of four potsbelongto theLate class,the othertwo beingRoughtypes.On the

otherhand,for all of thegravesin the southernsectionof the cemetery,theRoughtypesmakeup 50 Vo

or in most casesfar more of the pottery.Thus,at Armant there is no part of the cemeterywhich is

dominatedby Marl clay pottery.However,this doesnot meanthat groupsof gravesdominatedby

Marl clay potterydo not occurduringthe Naqadaculture.On the contrary,largegroupsof graves,at

Elkab for instance,(Hendrickx 1994)and Hierakonpolis(Adams 1987)and even entirecemeteries

suchasthoseof Tarkhan(Petrie,Wainwright& Gardiner1913,Petriet9'1.4),Tura(Junkerl9l2) and

Abu Roash(Klasens1957-61)arecompletelydominatedby Marl clay pottery.Only the transitionin

from 'Rough'to 'Late'potteryshouldbe placedlater.

dominance

Besidestheseproblemsconcerningthe main structureof the Stufm chronology,a few problems

relatedto particularStufenhaveto be mentioned.At first, the distinctionbetweenStufeTaand Ib is

apparentlybasedon the contentsof a numberof glavesfrom sitesfor which no cemeteryplan is

published(Abydos,el-Amrahand Mahasna,cf. Kaiser 1957:73-4).Fifteengraves,containing37

objects,areattributedtoStufeIa and27 gravescontaining66 objects,to StufeIb. Althoughthereis a

differencebetweenthe groupof objectsattributedto eachof the Stufen,it must alsobe noticedthat

severalrypes(B 22b,8 22 f ,B 26b,P 1 a, P 17)occurfor bothStufen.This,togetherwith thelimited

numberof dataand the fact that the spatialdistributionof the objectscannotbe controlled,seemsto

indicatethattheStufenIa andIb shouldbetterbeconsideredasanentity,aslong asno furtherevidence

is available.

Anotherproblemis causedby the relationshipbetweenKaiser'sStufentrd2 andIIIa1, which share

the sameWavy Handledtypesand differ mainly throughthe presenceor absenceof Black-Topped

types,andthroughtheir Decoratedtypes.Also of importancearethetransitionsfrom R 84-86to L 30

of restricted

b,c and from P 40 gl andP 40 el to P 40 q andP 46 blArm, as well asthe appearance

bowlse 2a q. However,whenlooking at the importantDecoratedtypeswhich Kaiser(1957:tt.23)

givesastypical for Stufetrd2, it appearsthatthereis not a singlegravewhereoneof theseDecorated

typesis presenttogetherwith a Black-Toppedtype and a Wavy Handlejar typical for StufeIId2.2

while the frequently

Among the other significanttypes,severalof them occur only occasionally,3

occurringtypesR 84-86 and L 30 b,c are relatedto eachother and belongto a $oup of typesinto

which Petrieapparentlyallowedimportantvariations(cf. p.a5). It is thereforeto be fearedthat the

attributionof a vesselto one of thesetypesby excavatorsother than Petriemay have been rather

arbitrary.Also the spatialdistributionat ArmantCemetery1400-1500easilyallowsa differentclustering of graves,by which the groupdefinedby KaiserasStufeIId2 no longerexists.Finally, sincethe

WavyHandledtypes,from the momentof theirfrst appearance

duringSrufenc until their disappearing at the endof the First Dynasty,alwaysseemto displaythe fastestevolutionof shape,it would be

very strangeif this would not alsohavebeenthecaseduringStufeULdZ-lIIal. For all thesereasonsthe

archaeological

descriptionof theStufenIId2 andIIIaI cannotbe maintainedin the way it was defined

by Kaiser.

The reasonfor the confusionbetweentheStufentrd2 and trIal probablyoriginatesfrom Kaiser's

analysisof theArmantcemetery.

The distinctionbetweentheStufentrIal andIIIa2 causesa particular

problem.First it shouldbe noticedthat on the spatialdistributionmapwherethe gravesbelongingto

eachStufeareshown(Kaiser 1957: tf . 20 C), thesymbolsindicatingrespectivelyStufelfral andItra2

haveerroneouslybeeninterchanged.

This wouldnot be a realproblemif it did not suggestthat it is the

latterStufe,at the extremesouthernlimit of the cemetery,which is represented

by only threegraves

(1558,1.559,1594;

part

of the cemeterywhich

and onemoreisolatedgrave,1578,in the northern

howeverhasnot onetype in commonwith the otherthreegraves).Looking at the spatiaidistribution

with this correctionin mind, itrs StufeIIIai whichis represented

by just threegraves,thetwo richest

4l

�of them containingWavy Handledtypes(W 41) which are closelyrelatedto thoseoccurringfurther

north (cf. Kaiser 1957:d. 16 B) in the groupsof gravesauributedby Kaiserto Sufe trd2.As already

Nile Silt potteryis dominantfor the entiresouthernpart of the cemetery

mentioned,straw-tempered

just asit is for Kaiser's StufeIJdZgraves.Therefore,it seemsappropriateto omit the four gravesfrom

group.

SrufeVIal asa separate

at Armant cemetery1400Next we haveto tum to theStufentrIb-Itrc3, which are not represented

1500.StufeIIfb wasalreadydefinedin Kaiser'soriginalpublication,the morerecentperiodhowever

was originally describedin anotherway. Startingwith architecturalinformation,inscriptionsand arthreeperiods,calledHorizonten(Kaiser1964:92-6;Ka'material,Kaiserdistinguishes

chaeological

ser& Dreyer 1982:260-r.4 The definition of theHorizontendoesnot rely on spatialdistributionand

is thereforeof a differentorderfrom the Stufenchronology.With regardto the pottery,theHorilonten

aredescribedas follows (Kaiser& Dreyer 1982:264):

largejars 74b,75 q-v.

HorizontA (beforeIrj-Hor):W 80 andsimilar'protodynastic'types;

Horizont B (Irj-Hor - Narmer):cylindricaljars with and without incisedwavy decoration,but the

secondgroupincreasesin number('protodynastic'type 50); largejars as for previousgroup with

additionaltypes76 and75 a-o.

Horizont C (startingwith Hor-Aha):cylindricaljars without inciseddecoration;largejars mainly

belongingto fype 76 or 75 a-o.

descriptionof the Horizontenittmmediatelybecomesclear thatHorizont

From the archaeological

A can be identifiedwith Stufelnb. The differencebetweentheHorizontenB andC is lessobvious.

The informationfrom which Kaiser startsis very limited sincehe dealsonly with gravesin which

havebeenfound.However,thisis notthemainproblem.ThedistinctionbetweenHorizont

serekhmarks

B andHorizontC is particularlydifficult to makesincethereareno typesof objectswhich arecharacteristicfor eachindividualHorizont,andthedifferencecanonly bemadethroughthe frequencyof the

'Wellendekor'(proto-dynastic74b,75 q-v) occuronly

sametypes.Also, thediagnostictypeswith

very exceptionally.At Tiarkhanonly 8 examplesarepresentamong5138pots.s

RecentlyKaiserextendedtheStufenchronologyup to theendof theSecondDynasty(Kaiser1990:

andthreeStufen,Itrc1,IIIc2 andIIIc3, wereadded.

Abb. 1). Stufeffibwasdividedinto two subphases

the chronologicalstagesdistinWith the latetypesof theWavy Handledclassasmain characteristics,

in

table7.6

guishedby Kaiseraresummarised

ThedistinctionKaisermakesbetweenStufeffibI andIIIb2 doesnot seemjustified, sinceat Tiarkhan,

for

for instance,there are226 gravesin which oneof the typesoccurswhich shouldbe characteristic

46

(i.e

belonging

to

the

and

types

graves

50

Vo)

(48

of

these

over

s,t or 49 d,l), whilst in 116

Snfe nlb}

47 series(Snfe Itrbl) arealsopresent.Furthermore,the spatialdistributionof the two groupsof types

showsno obviouspatterning(seealso p.59) and the very obviousspatialdistribution of the Turah

types.

cemeterydoesnot supportthi ideaof a chronologicaldifferencebetweenthe above-mentioned

This view might be supportedby the observationthat the differencebetweenthe rypesbelongingto

the47 seriesandtypes48 s,t| 49 d,l is not a differencein the shapeof thevessels,nor evenin the shape

or importanceof thedecoration,but only in thetechniqueby whichthedecorationwasapplied.Therefore, and alsoby virnreof the fact that StufeIIIb2 coversa very limited period of time accordingto

Kaiser(cf. Kaiser 1990:Abb. 1), it is preferableto makeno distinctionbetweentbeStufentrIbl and

Itrb2.

Kaiser's Stufefrcl consistsof types which are partly characteristicof StufeItrb2 and partly of

'transitionalperiods'within the evolution of the Naqada

Stufelnc1. The existenceof thesekinds of

culturecanof coursenot be denied,but it shouldbe questionedwhetherit is necessaryto distinguish

a periodfor which thereareno characteristicanduniquetypesof objects.This is especiallytrue since

the archaeological

descriptionof theStufenis oftenusedfor datingindividual gravesor evenobjects.

It thereforeseemsbetterto distinguishfewer periods,and admittedlyhaveeventuallya slightly less

detailedideaof thechronologicalevolutionof a cemetery,whilst on the other handarchaeologically

A1

-z

�distinctchronologicalphaseswill offer far betterpointsof comparison.

Finally we shouldpay attentiononcemoreto Kaiser's1957article.In this study,the descriptionof

theStufenis illustratedby plateson which the mostimportantandcharacteristictypesof objectsfor

eachSnfe are drawn (Kaiser 1957: tf . 2I-4) . Theseplateshave beenreproducedor referredto in a

large numberof srudiesdealingwith the Naqadaperiod.However,the relationshipbetweenthese

platesand the study of the Armant materialis not obviousat all. The platespresent2M types of

atArmant.Theother 125 typescomefrom

ponery.Of theseonly 119 - lessthanhalf - arerepresented

were

by

Kaiserto a particularSrufe,but this is not

which

allocated

in

cemeteries

found

other

graves

these125are the largemajority of

Among

basedon the horizontalstratigraphyof thesecemeteries.

White Cross-lined,DecoratedandWavy Handledtypes,which areoftenusedasdiagnosticwhenthe

or when attemptsare madeto comparefresh

relativechronologyof the Naqadacultureis discussed,

at Armant, 37 out of IL2, i.e.32,8 Vo,lta

datawith theStufenchronology.For the typesrepresented

given by Kaiseras characteristicfor morethan oneStufe,while the figure is only 13 out of 125,i.e.

atArmant.Furthermore,in a numberof cases,theassignlO,4Vo,for thepotterytypesnot represented

mentof potterytypesto a certainStufedoesnot correspondbetweenthe platesandthe resultsof the

atArmant,amongthemthreeout of the

Armantsfudy.This is truefor 34 7 out of 112typesrepresented

plates

shownby Kaiserhaveto be regarded

that

the

obvious

It

is

therefore

Handled

types.

Wavy

five

with greatprudenceandcertainlycannotbe consideredasabsoluteguidelines,as occurstoo often in

the literature,sincethis was not Kaiser's intention,and the platesare only to be consideredas an

idealisedoutlineof the developmentof theSufen.

4. The presentinformation available for cemeteriesbelongingto the Naqada culture in Upper

and Lower Egypt.

SinceKaiser'sstudyin 1957,an importantquantityof dataon predynasticandearlydynasticcemeteralreadyexcavatedin UpperEgypt during the first two

ies hasbecomeavailable.Severalcemeteries,

E.J.Baumgartelpublished,after long andpainsdecadesof this century havesincebeenpublished.8

cemeteries(Baumgartel1970b,correctionsand

from

the

Naqada

work,

corpus

objects

taking

the

of

supplements

Payne1987,Hendrickx1986),which howeverwill alwaysremainincompletesincea

largenumberof objects,mainly Roughtypes,remainedin the field. The publicationby B. Adamsof

Garstang's

excavationat theFort Cemeteryof Hierakonpolis(Adams1987),andof the othercemeteries at Hierakonpolisexploredby Quibell andGreen(Adamst974a),is mostimportantsinceno cemeteryfromthis major sitehadbeenpublishedpreviously.More informationconcemhg Hierakonpolis

anda numberof othersitesbetweenEsnaandGebeles-Silsilacomesfrom the work of H. deMorgan

in this areaduring the beginningof the centurt, also publishedrelatively recently (Needler1984,

Cleyet-Merle& Vallet 1982).The editionby Dunhamof Lythgoe'snoteson cemetery7000at Nagaed

Deir (Lythgoe& Dunham1965)is of coursevaluable,but doesnot allow a detailedidentificationof

the gravegoods.

This however,is suppliedby Friedman(1981),while the humanremainshavebeen

publishedby Podzorski(1990).Dunhamwasalsoresponsiblefor thepublicationof an earlydynastic

cemeteryatZawiyetel-Aryan,excavated

by FisherandReisnerin 1910(Dunham1978).

Importantinformationcomesfrom excavationswhich had alreadytakenplaceduring the decade

beforeWorld War II, but especiallysincethe end of the fifties.gBetween1957and 1959A. Klasens

excavated,

on behalfof theLeidenMuseum,severalearlydynasticcemeteriesat Abu Roash(Klasens

1957-1961).

in 1965-8at el SheikhIbadawherea smallearlydynastic

More recentarethe excavations

cemeterywasdiscovered(Zimmerman1974)andin 1966-7by theEgyptianAntiquitiesOrganisation,

underthe direction of A. el-Sayed,of a predynasticcemeteryat Salmany,nearAbydos (el-Sayed

1979).Thesurprisinglyrich resultsof theexcavations

Institut(DAI)

Arcfuiologisches

of theDeutsches

at Umm el Qaab,which startedin 1977andaredirectedby G. Dreyer(e.g.Kaiser& Grossman1979;

Kaiser& Dreyer 1982;Dreyer 1990, 1992U1993)are of courseof the utmost importancefor the

connectionbetweenthe Naqadacultureand the historicalperiod.A NaqadaIII cemeteryof limited

extentwas excavatedby the author at Elkab between1977 and 1980,on behalf of the Comitdde

FouillesBelgesenEgypte(Hendrickx1994).Across

the Nile, at Hierakonpolis,a numberof cemeter-

43

�ieswereinvestigatedby theHierakonpolisProjectunderthedirectionof thelateM. Hoffman( 1982a).

Finally, for Upper Egypt,therearethe excavationsof theInstitut Frangaisd'Arch4ologieOrientale,

et al. 1990;l99I; 1992;1993b;1994).In

at Adarma(Midant-Reynes

directedby B. Midant-Reynes

the Memphite are4 a few early dynasticgravesfrom North Abu Roashwere publishedby Hawas

(1980),while the apparentlyfar more importantcemeteryfrom the sameageat Abusir has only revondenDriesch& Eissa1992;Leclant& Clerc 1992).

centlybeenfound(Radwan1991;Boessneck,

In recentyears,a considerablenumberof excavationshaveshednew light on the relationof the

NaqadaculturebetweenUpperandLower Egypt.l0Besidesthevery importantMunich excavationsat

Minshat Abu Omar in the EastemDelta, which startedin 1978 and are under the direction of D.

Kroeper1988;1992),onehasalsoto

WildungandK. Kroeper(e.g.Kroeper& Wildung1985;1994:mentionthe limited numberof gravesfound at Tell Ibrahim Awad (van den Brink 1988b:77-II4:

I992c:50-1),BeniAmir andTell el-Masha'la(Krzyzaniak1989,el-HaggRagabI992),EzbetHassan

Dawud(el-Hangary1992)anda numberof othersites(cf. Krzyzaniak1989).Importantnew information hasalsobecomeavailablefor Nubia,ll but this falls beyondthe scopeof the presentarticle.

5. Problemsrelated to the published data 12

despitetheimportanceof all this new information,it is obviousthatthe old excavations

Nevertheless,

still representthe majority of the dataavailable.Therearetwo fundamentalproblemsfor re-studying

theseexcavations.The first oneis that,in manycases,no mapof the cemetery,or only an incomplete

one,hasbeenpublishedandit thereforebecomesimpossibleto studythe spatialdistributionof objects

The secondis that the cemeterieswere,in the bestcases,published

characteristics.

or archaeological

by graveregisterswhich referredto typologicalsystems.Thegreatmajorityof the originalobjectsare

neitherdescribednor drawn.The objectsthemselvesareno longeravailablefor studyin their totality,

and they will neverbe accessibleagainsinceonly a (limited) numberof themhavefound their way

hasbeenlost.An important

into museums,andeventhenin manycasesthedetailsof theirprovenance

numberof vesselswhich were lessattractivefor the museumswere left in the field. Therefore,one

inevitablyhasto rely on thepublishedgraveregistersandthetypologicalsystemsto which theyrefer

(cf. SeidlmayerI99O:24).

'predynastic'(PetrieI92l), the'protodynastic'(Petrie1953)and

Threetypologicalsystems,the

'archaic'

(Emery1938-58,Klasens1957-6I),haveto bediscussed,

althoughmorehavebeenused

the

(Reisner1908:90-9;Reisner& Firth I9I0:314-22;JunkerI9l2:31-44; Junkerl9I9: 48-79,Scharff

1926:16-35).All threeof themare descriptivetypologies,to which typescould alwaysbe added.

The 'predynastic'typologywasflrst developedby Petriefor his excavationsat NaqadaandBallas

(Petrie& Quibell 1896).At thattime hedistinguishedabout300potterytypes.However,afterexcavations at other sitesby himself and others,the numberof types was augmentedto 1718 when the

'predynastic'corpuswaspublished(PetrieI92l). Finally, after additionsby otherexcavators,a total

of almost3000 typeswas reached.l3The real significanceof this enormousnumberof typesis very

difficult to evaluate,sincePetrieneverdescribedthe criteria usedfor distinguishinga type from a

on severaloccasionsthat 'needlessmultiplications'shouldbe avoided

relatedone.He only stresses

(e.g. Petrie t92l: 5). As a result, it is to be expectedthat the definition of types,and thereforethe

additionof new typesto the corpus,was not applieduniformly by all excavators.It is most obvious

that Brunton, when publishinghis excavationsat Badari (Brunton & Caton-Thompson1928),

Mustagedda(Brunton 1937)andMatmar (Brunton 1948),recognisednew types more readily than

earlier(seealsoKaiser1957:76,note10).14

Petriedid somedecades

thecemeteries.l5

1553wereusedforthepublicationof

Outof about3000distinguishedtypes,only

The greatdifferencebetweenthesenumberscameaboutfor variousreasons.Oneof the mostimporwere readily madeinto separate

tant is that pots with decoration,or otherparticularcharacteristics,

types,but a large numberof them had beenpurchasedratherthan excavated,and thereforedid not

featurein an excavationreport.The fragmentarygraveregisterof the Naqadacemeteriesis another

reasonwhy a numberof publishedtypesarenot represented.

The relationbetweenthenumberof typesandthenumberof examplesknownfor eachtype,shows

A A

�importantdifferencesbetweenthe potteryclassesdistinguishedby Petrie(table3). The numerically

PolishedRed,Wavy Handled,Rough,Late) also show the

*"il-r"pr"r"nted classes(Black-Topped,

(White

highestrarioper type,between4 and7 examples,while thenumericallylessdominantclasses

by 1 to 2 examplesper type only. This

Cioss-lined,Fancy,Black Incised,Decorated)arerepresented

with particularshapes,areto

pottery,

orpottery

decorated

of

classes

indicatesthatthetypologiesof the

be regardedas an almostcompletecorpusratherthan a typologicalsystem.Wheneverthe individual

excavationreportsare examined,even strongerdifferencesappear.It is obvious,for instance,that

petriedistinguishes

far fewerRoughtypes,andthereforewill havea far largernumberof examplesfor

eachof thesetypes,thanBruntondoes.An obviousexamplearethesubtypesdistinguishedby Brunton

for the very frequentlyoccurringlarge,pointedjar R 81 (Brunton1927:pl. XLtr), which were apptlrently consideredasoneuniform rypeby Petrie'

% typs

frequency

# types

# examples

% examples

L

2

3

4

5

6

7

740

222

139

1

5

5

7

740

444

417

10,35

6,21

5,83

5,09

3,84

3,77

3,62

3,58

2,89

1,82

10,21

7,84

8,49

3,L3

6,54

6,88

3,74

1,75

1,15

3,31

47,65

14,29

8,95

5,86

3,54

2,90

2,38

2,06

1,48

0,84

3,67

100,00

100,00

8

9

10

11-15

16-20

2r-25

2644

31-40

41-50

5l-60

6r-70

82

237

total

9

5

4

3

3

2

(1)

Q)

(3)

(4)

2

3

13

57

31

26

8

t4

11

5

2

l

l

1553

3&

275

270

259

2s6

207

130

730

561

607

224

468

492

265

125

82

237

7r53

2rW

r,67

0,52

0,90

0,71

0,32

0,13

0,06

0,06

Tab. 3. Frequenciesfor Petrie's "predynastic"typology (cf. note 16).

( 1 ) :B 57 b; R24 a; R 85 h; W 19;W 43 b.

(2):P 2 2 a ; R 2 2 a .

(3):R 84.

(4):R 8 1 .

The numberof examplesknownfor onetype may differ greatly(table3). Typesof which only one

exampleis knownrepresent47 Voof thetypesbut only 10 Vaof theexamples.Some89 7oof the types

occurlessthan 10 times,representing

45 Voof the pottery.The 11 Voof thetypeswhich occur 10 or

more times represent55 Voof the pottery.The unique 'types' are lessexceptionalthan the figures

suggestsincethey arepart of seriesof relatedtypes(cf. Seidlmayer1990:9).

'predynastic'typology.First, confusion

Finally, somepracticalproblemsshouldbe notedfor the

exists in the numberingof the typesbecausePetrie renumberedpreviouslypublishedtypes when

integratingthem into his corpus.A numberof thesealterationswerementionedby Petrie(1921:pl.

LX), but otherswerenot (Hendrickx1989,II: 33-5;Patchl99l: 177-8).Secondly,if thepotteryfrom

new excavationsis to be identifiedwith the Petrietypology for comparisonwith the old excavation

45

�reports,this is not only hamperedby the fact that the 3000 types are scatteredover a numberof

publications,but also by the small scaleand abbreviateddetailsof the drawings.Also, it would be

usefulto investigatetheaccuracyof thedrawings,a taskwhichshouldbepossiblesincea largeamount

of the drawnpotteryis presentlyin thePetrieMuseumof EgyptianArchaeology.

of Tarkhan(Petrie,Wainwright

The 'protodynastic'typotogywasfrst developedfor thecemeteries

& Gardiner1913;Petrie l9I4). The original typology of Tiarkhanconsistsof 527 types,which had

'protodynastic'

published(Petrie.

corpuswasposthumously

to 885 by the time the

beenaugmented

1953),on which occasiona numberof the originaltype identificationsfrom Tarkhanwere changed.

The additionsby

The additionaltypesarealmostexclusivelyfrom theroyal tombsat Umm el QaaS.16

T

which

brings

the total to 1119

included,l

were

not

234

types,

otherexcavators,representinga further

known

Thenumberofexamples

of cemeteries.18

forthepublication

fypes.Outof these,743wercused

when comparedto the 'predynastic'

for each of the types (table 4) showsdifferent characteristics

frequency

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11-15

rG20

2l-25

2G30

31-40

41-50

51-60

6r-70

71-80

81-90

91-100

101-150

151-200

339

total

(1 )

Q)

(3)

(4)

(5)

(6)

a

(8)

# types

# examples

% examples

301

136

67

35

4l

27

L7

19

7

4

27

l5

11

6

8

3

6

I

2

I

I

2

5

I

301

272

140

205

162

119

152

63

40

328

263

260

168

269

r37

320

67

155

84

94

223

865

339

5,76

5,20

3,85

2,68

3,92

3,10

2,28

2,91

l,2l

0,77

6,28

5,03

4,97

3,21

5,15

2,62

6,L2

L,28

2,97

1,61

1,80

4,27

16,55

6,49

743

5227

100,00

20r

typology(cf. note19).

for Petrie's"protodynastic'

Tab.4. Frequencies

(1)a

: 6p ; 4 7 h ; 4 8 s ; 4 9 e ; 6 3 e ; 6 6 i .

( 2 ) : 5 9p .

Q): 47 p; 60j.

(4): 60 m.

(5):a6 k.

(6): a9 L 60 g.

Q): a6 d; 46 f; 46 m;49 d; 60 d.

G): a6 h.

46

% trypes

.

40,51

18,30

9rM

4,7L

5,52

3,63

2,29

2,56

0,94

0,54

3,63

2,Q2

1,48

0,8 1

1,08

0,40

0,8 1

0,1 3

0,27

0,13

0,13

0,27

0,67

0,13

100,00

�typology.Typesfor which only oneexampleis knownrepresent40 Voof thetypesbut not even6 Voof

by lessthan 10examples,makingup 3l Voof

thepottery.A total of 87,5Voof thetypesis represented

the pottery.T'he12,5Vaof thetypeswhich occur 10 or moretimesrepresent69 Voof thepottery.

no classesof pottery,since,accordingto

typology(Petrie1953)distinguishes

The 'protodynastic'

into theearlydynasticperiod.However,

Wavy

classes

continued

and

the

Handled

the

Late

only

Petrie,

with regardto theceramicfabric.This,

it hasalreadybeenseenthattheLate classis not homogeneous

of course,causesconfusionbetweenthewell-madepotteryin Mari clay andtheRoughpottery,mostly .

Nile Silt. Sincethe publisheddrawingsare small and similar fypes are

madefrom straw-tempered

known to occurin both ceramicfabrics,in a limited numberof casesit cannotbe decidedto which

categorya particularvesselbelongs.

A particularproblemis raisedby the confusionwhich is apparentwithin the group of cylindrical

jars, which are the descendants

of theWavy Handledclass.Petrieusesthe shapeof the wavy handle

decorationitself as the main criterionfor distinguishingtypes(Petrie,Wainwright& Gardiner1913:

pl. XLD(), while the differencesin shapeof the vesselsareconsideredto be only of secondaryimportance.This results,for instance,in importantdifferencesin shapebetweencertainvesselswhich areall

artributedto type 46 d (Petrie1914:pl. XXVil). As for the publisheddrawings,the sameproblems

'predynastic'corpus.

occurasin the

The 'archaic'typologywasdevelopedby W.B. Emeryfor thepublicationof thefinds from thelarge

at Saqqara(Emery1938-58).Thistypologyhasbeendevelopedin a morestructuredmanner

mastabas

'predynastic'

and 'protodynastic'typologies.On theotherhand,anindisputabledisadvantage

thanthe

is that Emery limited the numberof typesby allowing a considerabledegreeof variationwithin one

type.Unfornrnately,this cannotbe checked,sincethe originalobjectsarenot availablefor study,and

becauseEmery in his 1949,1953and 1958publications,usesa set of standarddrawingswhich are

alwaysrepeatedfor illustratinghis finds.Comparisonwith Emery 1938,beforethesestandarddrawingswereused,makesit clearthat importantdifferencesoccurbetweenvesselsattributedto the same

type (e.g.typesA 3 andA 4). As a result,it is not clearif thereis any real valuein the standardisation

by Emery'spublications.

of the gravegoodssuggested

at Abu Roash

The 'archaic'typologywasenlargedby A. Klasenstheon occasionof his excavations

(Klasens1957-61).Klasensaddsanimportantnumberof typesto the alreadyexistinglist, despitethe

This is onemore

factthatthenumberof objectswasfar smallerthanthosefoundby Emeryat Saqqara.

indicationof thevariationEmeryallowedwithin thetypes.Whenconsideringtherelationbetweenthe

numberof types and the numberof objectsfor the cemeteriesat Abu Roashalone (table 5), it is

only 5 Voof thepottery,whilst 81 7o

remarkablethat42 Voof thetypesoccuroncebut this represents

of the typesoccur lessthan 10 times,representing

25 Voof the pottery.The 19 Voof the typeswhich

occur 10 or more times represent75 Voof the pottery.The drawingsof the objectspublishedby

Klasens,althoughreproducedon a smallscale,areof farbetterqualitythanthoseof Petrie'stypologies.

Also,Klasenspublishesa largenumberof examplesfor eachrype,which helpsconsiderablyin understandingthe principlesby which the typologywasestablished.

havebeenfound,amongwhich

Besidespottery,an importantnumberof othertypesof gravegoods

arestonevessels,palettes,beads,etc.However,thetypesarerepresented

in suchsmallnuinbersthat

they offer only limited possibilitiesfor comparisonbetweengraves.Thereis one exception,namely

thestonevesselsfromAbu Roashpublishedaccordingto theprinciplesusedfor the 'archaic'typology

(Klasens1957-61).Although89 Voof thetypesoccurlessthan 10 times,this represents

only 50 %oof

thevessels.Thus,the remainingll Voof thetypesmustalsorepresenthalf of the numberof vessels.

6. Statusquaestionisof researchon the relative chronology of the Naqadaculture since Kaiser

1957.

Only a few studies,the most extensiveof them as yet unpublished,havetried to check,corrector

amendKaiser'sStufenchronology.For thetime being,theycanbe dividedinto two groups:thosewho

areusingcomputer-based

multivariateseriationandthosewho areprimarily relying on the studyof

spatialdistribution.For a studymentionedby Vertesalji(1988),no informationis available.

47

�# types

frequency

t a l

lLl

I

2

3l

27

l9

15

7

8

a

J

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

I 1-15

t6-20

2r-25

26-30

31-40

41-50

51-60

6L-70

71-80

81-90

134

137

a

J

a

J

(1)

(2>

9

8

t0

5

5

9

2

I

1

I

0

(3)

(4)

(s)

J

# examples

% examples

12l

62

81

76

75

1a

+z

56

)4

27

90

103

r82

111

t39

308

96

56

62

0

256

1

< a

I

I

137

lJ+

5,41

2,77

3,62

3,40

135

1,88

2,50

1,07

l,2l

4,02

4,60

8,13

4,96

6,21

13,76

4,29

2,50

2,77

0,00

11,30

5,gg

6,L2

types

41,97

10,73

9,34

6,57

5,19

a

L tA

a L1

7,77

1,04

1,04

3,1I

2,77

3,46

L,lJ

|

/ 1

3,11

0,69

0,35

0,35

0,00

1,04

0,35

0,35

for Klasen's"archaic"typologyat Abu Roach.

Tab. 5. Frequencies

(l): A 3.

(2): K 2.

( 3 ) :B 8 ; L 7 ; W 7 .

(a): B 10.

( 5 ) :J 1 .

A studyby E.M. Wilkinson (1974),dealingwith seriationtechniques,which are,as a test,applied

Threeseriationsarecarriedout (Wilkinson

to theArmantcemeteryis only of historicalimportance.19

1974 87).Whencomparedto the spatialdistribution,theresultsof all threeseriationsarecompletely

eventhe one using Kaiser'soriginal orderas startingorder.20Also, no archaeological

unacceptable,

evaluationof Kaiser'sresultsis made.

More importantis the articleby B.J. Kemp (1982),wherethe seriationby multi-dimensionalscaling of the graveswithin cemeteryB at el-Amrahandthe cemeteryof el-Mahasnais discussed.However,it shouldbe mentionedin advancethat the seriationis not usedfor the evaluationof Kaiser's

Dating.First, Petrie'spottery corpuswas condensedto 43

Stufenchronology,but Petrie'sSequence

Accordingto the excatypes,unfortunatelywithout mentioningwhich typeshavebeenamalgamated.

at el-Amrahcemetery

vationreport(Randall-Mclver& Mace1902),228 potterytypesarerepresented

B. Out of 90 gravesfor which informationis available,70 could be seriatedbecausethey contained

types.After seriation,Kempdistinguishesthreegroupsof graves(Group

two or moreof thecondensed

'transitional'groups.

Thetransitionalgroupsrepresent17graves,i.e.24Voof theseriated

I-Itr) andtwo

gmves.If comparedwith Kaiser'sdatingof the gravesat el-Amrah(Kaiser 1957:73),Group I correspondswith Srufel-trc. The transitionalgroupbetweenGroupI andGroupII matchesStufellc (except

grave210 -ndz), while Group II, as well as the transitionalgroup betweenthe GroupsII and trI,

correspondswith Stufetr-Ild2. None of the gravesfrom GrouptrI is datedby Kaiser,but the objects

for his StufeIlIb. Thechoiceof el-AmrahcemeteryB seemsrather

from thesegravesarecharacteristic

unfortunate,sinceit may well be that the entirepredynasticperiod was coveredby the cemetery,as

(Randall-Mclver& Mace 1902:3, seealsoKemp 1982:7-12),but only 98

statedby the excavators

48

�gravesout of about400 havebeenpublished,andamongthe publishedgravestherearenonecharacteristicfor StufeIIIaI (exceptgmve22I) andnla2, as alreadystatedby Kaiser(1957:73).Kemp's

questionwhethera periodis missingat el-Amrah(Kemp 1982: L2) canthereforebe answeredposiit is to be expectedthat the

tively, as far as the publisheddata are concerned.As a consequence,

very

distinct.

separationbetweenKemp'sGrouptr andGroupIII is

potterytypesarenot

Kemp,of course,alsonoticedthata numberof well-knownandcharacteristic

at el-AmratrcemeteryB, andtherefore,a similar studywasmadefor the cemeteryat elrepresented

Mahasna,where313ponerygpes areidentifiedin the excavationreport(Ayrton&Loat 1911)and

informationis availablefor 131graves.The potterytypesare condensedto 38 typesafter which 98

gravescould be seriated.Threegroupsof graveswith two transitionalgoups are also distinguished

for el-Mahasna,but this time the transitionbetweenthe Groupstr and III is lessmarked,indicating

that the cemeterywas in continuoususe.Comparisonwith Kaiser's Snfen chronologyis diffircult

gtavesfromMahasna(Kaiser

1957:74).Nevertheless,

sinceKaiserdatedonlyarestrictednumberof

GroupI seemsto matchwith StufeIb-Ic, thetransitionbetweenGroupsI andtr with StufeIIa-IIc, and

Group tr with StufeI[c-nd2. The transitionbetweenthe Groups tr and Itr as well as group Itr itself

seemsto be coveredbyStufeIIIaI-IIIb, althoughKaiserdatedonly threegravesof this Group.

between

Apart from the 'missing'typesat el-Amrah,the threeGroupsshowstrongresemblances

with Kaiser'sStufenchronology.Finally Kemp

thetwo sites,asis alsoconfirmedby theconcordances

the validity of thethreeperiodswhich aretraditionallydistinguishedwithin thepredynastic

discusses

culture.Becauseof his identificationof GroupItr at el-Amratrasearlydynastic,he distinguishesonly

two mainperiodswithin thepredynasticculture,despitethe fact thattheearlierpart of GroupIII at elMahasnastill belongsto the predynasticperiod.

A far more elaboratestudyof the relativechronologyusing seriationhasrecentlybeenmadeby

T.A.H.Wilkinson (I993Q.zt Eight predynastic- early dynasticcemeteries22wereseriatedusingthe

Bonn SeriationProgram.For the purposeof seriation,the typesfrom Petrie'scorpuswhich occurred

in the eight cemeterieswere condensedto 141 types.The use of a universaltypology for all eight

horizontalstratigraphy

cemeteries

alloweddirectcomparison

of theseriationresults.Whereverpossible,

was used to check the seriationresults.In all cases,the spatial distributionconfirmedthe phases

derivedthroughseriation.Eachindividual sequencewas comparedagainstKaiser'sStufenchronology.Significantdifferencesemerged,mostnotablyin Kaiser'sdemarcationof thethreemajorNaqada

culturephases.The eight individual site-basedsequences

were correlatedusing diagnostictypes,to

'chronological

producea

matrix' coveringLower,Middle and UpperEgypt during the predynasticearlydynastictransition.

Regardingthe problemsandpossibilitiesof seriation,somegeneralremarkshaveto be made.Obviouslythe variousproblemsconcernedwith thetypologiesusedfor thepublicationof graveregisters

will have consequences

for the applicationof seriation.As alreadymentioned,it is impossibleto

establisha newtypologicalapparatus,

moresuitedfor computerseriationthanPetrie's,sincethe original objectsareno longeravailable,nor arethey publishedin a marner allowingrenewedtypological

work. The main problemis that the numberof typesis very largewhile the numberof examplesof

thesetypesis generallyvery low (table3-4).Therefore,seriationseemsimpossiblewithout grouping

typesor usingonly a limited numberof frequentlyoccurringtypes.Limiting thenumberof typeswill

of courseresult in a tendencytowardsexplicit differencesbetweengrcupsof graves.On the other

hand,groupingtypesseemsperhapsevenmoredangerous,consideringthe alreadydiscussedheterogeneityof the criteriausedfor distinguishingtypeclassesas well asindividualtypeswithin thePetrie

typologies.More important,the variationallowedwithin onetype seemsto differ ratherimportantly

accordingto the interpretationof the individualexcavators.The unfortunateresultof this sinrationis

that the effect of combiningtypescannotbe checkedin an adequateway, and may well causevery

differentshapesandevenpotteryfabricsto endup asthe sametype.Nevertheless,

if seriationis to be

applied,carefulgroupingof Petrie'stypesseemsto be the only possibility.

A generalarchaeological

problemis thechronologicalvalueof seriation.In otherwords,thedifferencesbetweenthe groupsof relatedgravesshouldbe due to time and not to, for example,social

differentiationor foreign influences(cf. Mortensen1991: 15).Although,generallyspeaking,this is

certainlyan importantproblemfor interpretingtheresultsof seriation,theimpactof non-chronolog!

49

�Petrie

L92L

L10

L30c

L30k

L30m

L30s

L33m

L34 e

L36 a

L36a

L 36b

L36n

L37 m

L38a

L38a

L46

L58c{

w33

w35

w 33-35

w 33-35

w 33-35

W 5 1a

W 5 1a

w58

w58

w58

w58

w62

w62

w62

w63

WTla

W 7 1a

WTla

w80

w80

w80

w80

w85

w85

w90

w90

w90

w90

l*

Petrie

1953

3 m

55r

55n

55n

55s

56f

56f

60d

60m

60b

6og

65k

59b

59b

82c

86 d-f

Mf

47 b2

47 b5

47 b9

75s

43r

43s

46d

46t

46h

46k

46b

46m

46p

47b

46i

47p

48d

47r

47t

48s

49e

49d

491

50d

50d

50e

50f

5og

50s

50t

1 1b

57b

59d

59h

Emery /

Klasens

I'

Petrie

:n"

:

A3

A3

A3

c6

B8

:u

_

Petrie

1953

65p

749

74p

75a

75d

76a

76b

76c

76d

76e

76r

76m

76n

85d

85e

85f

822

822

E22

E.22

E22

i t-s

F 7-8

F 7-8

F9

F9

F9

F10

F10

Fl0

:'o

Flt

(F 1)

F12

F ll-12

F lr-12

(F 1)

(F 1)

K7

D3

B8

B8

Tab. 6. Table of typological concordancesfor characteristicpottery types.

50

Emery/

Klasens

C2

823

D 8

A4

A4

A6

A6

A7

A7

AL2

A 8

A8

A 8

E2

E2

E2

�for the Naqadaculture.Up to the presentmoment,

cal elementscan almostcertainlybe disregarded

(cf. Dreyer

the evidencefor foreign influenceon the Naqadacultureof UpperEgypt is very scanty

have

an imconsidered

to

be

cannot

andcertainly

1992a,Holmes lggzb,Adams & Friedmant992)

Wavy

of

the

pacton theresultof seriation.The only majorexceptionis of coursethePalestinianorigin

i{andled potter}, but this causesno real problemsinceonly the prototypes,which most probably

arrivedin UpperEgypt within a limited spaceof time, areto be consideredas foreigninfluence.The

morphologicalevolutionof theWavy Handledclasstook placein Egypt itself.

The impact of social differentiationupon the evolutionof potterytypes seemsmore difficult to

define.However,by looking at thecontentsof particularlyrich graves,itbecomesclearthattheseonly

occasionallycontainpotteryof exceptionalshapeor function.At the sametime it will be noticedthat

was expressed

throughthe quantifyof similar objectsratherthan

the socialpositionof the deceased

throughexceptionalobjects.23Although the existenceof thesekinds of objectswithin the graves

thattheywill haveno realimpact

cannotbe denied,their isolatedoccurrenceautomaticallyguarantees

on the resultsof seriation.

A questionwhich is very difficult to evaluate,but which might have considerableinfluenceon

seriation,is the estimationof theperiodof time betweentheproductionof thePotteryandthemoment

Thepotteryof the Naqadaculturewasnot madeespecially

whentheybecamepart of thegravegoods.

for the funerarybeliefs(cf. Hendrickx 1994:50-t1.2+Different functionswill causevariationsin the

spanof time duringwhich the vesselshavebeenused.Also, the excavationreportsnevermentionthe

conditionsof usein which the potterywasfound(cf. Hendrickx 1994:50-1,734).

A particularproblemfor seriationis raisedby Petrie'sdistinctionbetweenthe Roughandthe Late

class.The Late classincludesa numberof rypeswhich areboth in shapeandfabric closelyrelatedto

typesfrom the Rough class,but they are excludedfrom this classbecauseof their chronological

position.This shouldbe takeninto accountfor seriationsinceotherwisethesetypeswill causemarked

transitionswithin the generatedmatrix. Finally, the most obviousproblem for seriationis that an

availablesourceof information,i.e. the spatialdistribution,is not takenin account,or only usedasan

elementof control after the seriationhasbeencarriedout. As far as the authoris awale,no attempts

haveyet beenmadeto includethe positionof a graveinto the datausedfor seriation.

Besidesthe studiesusing seriationfor discussingthe relative chronologyof the Naqadaculture,

Oncemore,

thereis the secondgroupwhich startsfrom the spatialdistributionwithin the cemeteries.

discussedwith referenceto seriation,will occur,althoughto a

theproblemof groupingtypes,already

lesserextent.

The frst studyof this kind to be discussedis anunpublishedmasterof artsthesisby R. Friedman,

presentedat the University of Californiain 1981andconcerningthe sPatialdistributionand relative

chronologyat Nagaed Der cemetery7000(Friedman1981).Comparisonis madewith Kaiser'sSrufen

chronology.Spatiallydistinguishedgroupsof graveswith objectscharacteristicfor theStufenlc-trd

at Nagaed Der.Althoughgravesarcpresentwhich shouldbeplacedbeforeSrufe

arealsorepresented

Ic, it was not possibleto confirm Kaiser's differencebetweenStufela and Ib. Also, a numberof

differencesbetweenArmant and Naga ed Der are observed,the most importantbeing the massive

presenceof Black-Toppedwareduring Srufefrb.lnthis respectit seemsto be possibleto connectthe

(FriedmanI98l:745), wherea similarphenomcemeteryat Nagaed Der with the oneat el-Mahasna

by Kaiser(1957:74).

enonhadalreadybeenobserved

J. C. Payneapplied Kaiser's chronologyto the informationavailablefor the Main Cemeteryat

Naqada(Payne1990,1992).Sheconcludesthatthe sameSnfen canbe distinguishedboth at Armant

descriptionof theSnfen remainvery

andat Naqadaandalsothatthe differencesin thearchaeological

limited, the mostimportantbeing situatedn Snfe trb (Payne1990:81).

The gravesfrom the cemeteryat MinshatAbuOmarhavebeendividedby Kroeper(1988,Kroeper

& Wildung 1985:92-6,seealsoKaiser 1987)into four groups,somewith subdivisions,accordingto

Thesegroups,which vary stronglyin numberand whose

the burial tradition and the gravegoods.2S

spatialdistributionshowsno really obviouspattern(Kroeper& Wildung 1985:Abb. 315-21),certainly havea chronologicalvalue,but thedetailsarenot yet known, sincethe publishedreportis only

preliminary.Also, the relationbetweenthe relativechronologyat MinshatAbu Omar,in the eastern

Delta,andUpperEgypt shouldbe a point of greatcaution.

51

�vesselshavebeendividedby van den Brink (this volume)into four

Recently,the serelih-bearing

chronologicalgroups,startingfrom the serekhsthemselvesaswell asthe vesseltypesand the spatial

26'

distributionof the cemeteriesin which thesevesselshavebeenfound

Finally, thereis the author'sdoctoralthesispresentedat LeuvenUniversity in 1989,which deals

betweenAsyut andAssuananda part of which is devotedto theproblem

primarily with thecemeteries

-321)'Although the

of the relativechronologyfor the whole of Egypt (Hendrickx1989:239-46,257

full publicationof this study will have to wait for sometime, it seemsneverthelessappropriateto

'predynastic'cemeterieS

for which both a mapahd

discusssomeof theresults.The limited numberof

point.27

For the early dynastic

as

a

starting

a graveregister,evenif incomplete,are availableserved

'archaic'

'protodynastic'

cemeteriesin Lower Egypt.

and

period,informationcamefrom a numberof

18Ar fot the methodologicalprocedure,thereis not muchdifferencefrom the methodalreadydevelopedby Kaiser.This impliesthatthe distinctionof relatedgtoupsof gravesis basednot only on their

contentsbut also on their spatialdistributionwithin the cemetery.As a result,a conflict of interests

will arisebetweenthesearchfor closerchronologicalproximity of all examplesof onepotterytype on

the one hand,and the definition of spatiallywell-definedgroupsof graveson the other.Neither of

thesetwo elementscan be acceptedas prevailingover the other.Thus,most unfortunately,it seems

'objective' rules for the definition of archaeologicalcomimpossibleto establishclearly defined,

plexesrepresentingrelativechronologicalperiodswithin the Naqadaculture.The samemethod,applied by Kaiseraswell asby ourselves,is of courseultimatelyfoundedon the seriationprinciple,but

extenton the personalinterpretationof the researcher.

dependsin real termsto a considerable

By comparingthe cemeterieswhich were analysed,it becomesclearthat similar groupsexist for

different cemeteries.In that manner,11 groupsof graves,an equalnumberto Kaiser's Stufen,arc

distinguishedandtheir relativechronologicalorderdefinedthroughtheir mutualpositionin the cemeteriesand throughthe evolution of the potteryclassesand types of objects.However,comparing

doesnot haveto imply thattheyare

groupsof relatedobjectsfrom geographicallydifferentcemeteries

this questioncannotbe answered

terms.

Unforhrnately,

in absolutechronological

contemporaneous

14

from UpperEgypt (cf.

becauseof the limitednumberof C datesavailablefor theNaqadacemeteries

Hassan1984b,1985,Hassan& Robinson1987).For thisreason,andsincerelatedgroupsof archaeological objectscan be distinguishedat severalsites,we may as well, until any proof to the contrary

groups,meaningthat the same

of closelysimilararchaeological

emerges,acceptthecontemporaneity

At this stageof theinvestigacemeteries.

different

for

the

existed

well

have

periods

may

chronological

integrated.

were

tion, the datafrom cemeterieswithout publishedmaps

Finally, after an investigationfor the possibilitiesof regionalvariability (seepp.61-3),a list of all

typesof objectswasmade,mentioningfor eachof themthe relativechronologicalperiod(s)in which

descriptionof eachof

This allowsan archaeological

they arepresentandthe numberof occunences.

the relativechronologicalperiods.

madeby Kaiserfor cemetery1400-1500atArmantarenot fundamentally

The generalobservations

contradictedand thereforethe numberof relativechronologicalperiodsis equal to the numberof

Snfen distinguishedby Kaiser,althoughin somecasesimportantdifferencesoccurin their archaeothoughit might causeconfusion,it was decidedfor the

logical description(cf. infra). Nevertheless,

'Stufe'by 'Naqada'andat the sametime

time beingto useKaiser'sterminologybut replacethe word

'NaqadaIA' etc.

changethe letterindicationinto capitalletters,which resultsin

Sincemy researchon the relativechronologywill haveto be enlargedwith the datafrom cemetery

for Kaiser'sSrufenIalb-IId, only

N 7000at Naqaed Der (cf. note 16),which seemto be characteristic

the NaqadaIII chronologywill be dealtwith further.

It has alreadybeendiscussedthat Kaiser'sdefinition of the Stufenlldz-IJJaz showsa numberof

problems(seepp.41-2),the most importantof which is that the distinctionbetweenKaiser'sSnfen

trd2 and IIIaI is not reliable,sinceneitherthe spatialdistributionnor the characteristictypesmentioned by Kaiser allow rwo periodsto be distinguished.Also, Kaiser'sdescriptionof StufeIna2 at

Armant, is basedon a very limited numberof graves;it is obviousthat the typesof objectsgiven by

Kaiser as characteristicfor StufefrIa2 (Kaiser 1957:tf . 24H*)arefar more numerousthan can be

for

deducedfrom theArmantcemeteryandthat theyarein fact largelyderivedfrom othercemeteries,

which the spatialdistributioncouldnot be investigated.

52

�dl

-

J

tll

d

J i ' * . - a

-\c)\c)\O\O;

'

o

'/

=

6

9 S 3 V q

f ; ;

; ; ; - ; ;

h 6 6 h

9

:

0

:

h

h ;

A ^ A

0

=

=

0

Q

O

E

x

fr l

G

O

-

x

€

=

'U

E

o

a0>

At

r- =-o

t nn\ O

r )

a

ao

C

<c

r -

€

3} } > , ,

N N N d 6 l C t

o 0 o u o o

!

L

g

L

L

!

o o o 0 q ) 0

< o D<a I

: x

- X

c

.

'C -t

a :

=

t

- / =

��.

=

t

^

D

oo

.

D

.

D*tr

. J

. 9 .

v

n

t r o

F

D

t

. - o

6

o

'

-.o

'

> . " o . .

h

o

o

o

o

. * - '

r

'

o

o

o

:

'

o

F ' o o '

A

,

o

.

.

h

O

o

.

.

-

. O

.o oo

o

o

o

'

o

o

c.t

J

O

O

O

o

o

o

-l

I

F.

I

iI

G

O

i

l!

o

J

O

O

U)

c.l

o o >

��=

*

\

3

{

o F

d%

q.b cq *o.. "o' o'.

ada

o ..13'

o. 8o

#r

. o€o

<t

€

L

'8.

. o 9b

.

'E

o :9

.3fft'=

o ' . . o o

o o o

c l ' c t

o '

o '

o

oo.

.f''a Eouo.

c 8

'o..'ro

.

'_

S.xX

de d i

o €-'

n

!

oo

-i;-iFiX

9 9 9 9 I

, a a r 8

-;

6

.o^8

&-

.

u .

F

zi

E

!

E

=

: ! ! :

I

I

F

O

? : c . .

B

.

_ ooo. o . " :^' "

&.'

o

'F

g se ' . -u

. ^!L

.' dd

.;.tf,

B...oo

c

. po tr

* .

a--.

. F

o

c

L

:""

o ' : g" -_' 9.g s . .o S

n

:

e.'3

l ;

rF8

,>7

o o o r

E'to;

3.'o +Eef o.

E

.'

E

I

olo-:

s5."9

.

! 5 5E 6

d 4 4 4 :

t-

.o5 !

,'*i;i"ii:i+"

e E O o

! cie !

9 r o o

v

o_

. ", " o.

€ ?

v

'

'- b

t

�When studyingthe spatialdistribution at the NaqadaIII cemeteryof Elkab (Hendrickx 1994:20516) four groupr of gruu"r could be distinguished,both by their contentsandby their spatialdistribugtaveswas

tion (fig. l). The homogeneityof the distributionof theWavy Handledtypeswithin these

groups

could be

two

IIIa2,

Srufe

quite rernarkable,and within materialcharacteristicfor Kaiser's

the

Stufenfrd2problemswith

Becauseof this observationandtheabove-mentioned

&stinguished.2g

was

readjustedto NaqadaItrAl

Snfefrl&'

Kaiser's

within

IIIal, the mostrecentgroupdistinguished

while most of the originalSrufelfral types,togetherwith a largenumberof the Snfe ild2 types,are

consideredcharacteristicfor NaqadaIJDZ.

In orderto link the relativechronologyof the Naqadaperiodto historicaltimes,the early dynastic

cemeteriesof Lower Egypt haveto be takeninto account,sincewell publishedlargecemeteriesfrom

this periodarenot availablefor UpperEgypt.The switchfrom Upperto Lower Egypt shouldnot be a

problem,sinceit is generallyacceptedthat,certainlyby Naqadam{z,the wholecountry

fund-amental

The cemeteries

was alreadya cultural entity and probablyalso politically united (cf. Kaiser 1990).

'archaic'

'protodynastic'

typologies,

and

involved (note 16) have beenpublishedaccordingto the

'predynastic'typolwith

the

if

compared

seriation

for

which offer a numberof statisticaladvantages

ogy (cf. pp.M-7).Therefore,it wasquite straightforwardto identify groupsof relatedgraves,starting

jars

from a timited number of characteristicpottery Upes, mainly storagejars and the cylindrical

which representthe final stagesof the evolution of the Wavy Handledclass.The evolution of the

cemeteryatTurahis particularlyclear.This wasnotedby theexcavatorhimself(Junker1912:1)' and

lateralsoby Kaiser(1964: 108-9).The spatialdistributionof this cemeterydisplaystbreeclearzones

by the differencein latetypesof Wavy Handledjars.3oThe southern

(fig.2),which arecharacterised

part of the cemetery(zone1) is dominatedby Junker'stypesLK-LXV (= W 8A 47 P), the central

pu.t 1ron" 2) by Junker'stype LX\n (= 50 d) andthenorthempart (zone3) by Junker'sfypesLXVII3l

L>Of (= 50 t). The spatialdistributionat TarkhanValleyCemetery is lessobvious,but still allows

two largegtoupsof tombsand two or threesmalleronesto be distinguished(fig. 3). The cemetery

'path' runningSW-NE.The frst group,dominatedby 46 b-h (= W

seemsto havedevelopedalonga

'path', with the mostmarkedconcenffa58-62),is situatedimmediatelyto the north and southof the

sections(zone1).The secondgroup,dominatedby47 p,48'49 (=

tionsin thecentralandnorth-eastern

in

W 71 a, W 80, W 85), is situatedfurtherawayfrom thepath,with the mostmarkedconcentrations

to

the

section

central

the

in

zones,

one

(zone

Two

small

2).