AT THE EDGE OF THE WORLD:

COSMOLOGICAL CONCEPTIONS OF THE EASTERN

HORIZON IN MESOPOTAMIA*

CHRISTOPHER WOODS

Chicago

It was on the banks of the Hyphasis that Alexander’s march through

Asia finally came to a halt. This was the furthest extent of his conquests, the terminal point of his campaign, the place where later

would stand a brass column bearing the inscription ΑΛΕ Α Ρ

Ε Αϒ Α Ε

“Alexander stayed his steps at this point.”1 He

would not cross that river. There would be no bridgehead on the

* This paper has its genesis in two earlier studies that are also concerned with

the Sun-god: “On the Euphrates,” ZA 95 (2005) 7-45; “The Sun-God Tablet of

Nabû-apla-iddina Revisited”, JCS 56 (2004) 23-103. I would like to express my

sincere gratitude to Monica Crews, John Dillery, Jennie Myers, Martha Roth,

Piotr Steinkeller, Theo van den Hout, and Irene Winter for their insights, suggestions, and assistance. I also thank P. Steinkeller for making available to me an

early draft of his “Of Stars and Men: The Conceptual and Mythological Setup

of Babylonian Extispicy”, in Biblical and Oriental Studies in Memory of W. L. Moran

(Biblica et Orientalia 48), ed. A. Gianto (Rome 2005) 11-47—this seminal article

influenced my thinking on this topic. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the

dissertation of J. Polonsky (“The Rise of the Sun God and the Determination of

Destiny in Ancient Mesopotamia” [University of Pennsylvania, Ph.D. 2002]), which

deals with much of the same evidence, but places it within a different conceptual

framework (see also now J. Polonsky, “The Mesopotamian Conceptualization of

Birth and the Determination of Destiny at Sunrise,” in If a Man Builds a Joyful

House: Assyriological Studies in Honor of Erle Verdun Leichty, ed. A. K. Guinan, et al.

[Leiden/Boston 2006] 297-311). Although her exhaustive study became known to

me only after the initial drafts of this paper were written, I was able to incorporate

a number of important citations from her work which have benefitted the present

version. Portions of this paper were presented at the 50th meeting of the Rencontre

Assyriologique Internationale (Skukuza, South Africa August 2nd, 2004).

Citations of Sumerian sources often follow The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian

Literature (http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/); those of the Epic of Gilgameš follow A. R.

George, The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts,

2 vols. (Oxford 2003). The abbreviations used are those of The Assyrian Dictionary

of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago and/or The Sumerian Dictionary of the

University of Pennsylvania Museum.

1

As claimed by Philostratus, following the translation of F. C. Conybeare,

Philostratus I: The Life of Apollonius of Tyana (Loeb Classical Library 16; Cambridge,

MA/London 1912) 228-229 (II.43); on the reliability of Philostratus in this regard,

© Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2009

JANER 9.2

Also available online – brill.nl/jane DOI: 10.1163/156921109X12520501747912

�184

christopher woods

far bank. Eight years had passed since crossing the Hellespont,

but here, on the Indian frontier, his men reached the very limits

of human endurance and refused to go on.2 And so Alexander was

forced to make his ill-fated return to Babylon. He was not destined

to reach the uncharted lands that lay beyond, lands that lay at the

edge of the map, upon whose shores, classical geographers were

sure, the waters of the cosmic river Ocean gently lapped.

So astounding was Alexander’s halt that it reshaped the classical imagination. India had long been held to lie at the end of the

earth, a land of marvels where reality gives way to fantasy and

where empirical and mythical geography blur. But with Alexander’s

campaign these vague notions took a more definite form with the

Hyphasis becoming something of a ne plus ultra, a perimeter of the

commonplace and the mortal beyond which lay the arcane and

the divine. In the legendary tradition that inevitably grew from

his conquests, Alexander’s failure to cross the Hyphasis came to

symbolize a failed quest for immortality and heavenly wisdom—an

allegory of man’s inability to transcend the limits of the human

condition.3 The eastern frontier is where, in the Greek Alexander

Romance,4 the Macedonian army becomes hopelessly lost in the

Land of Darkness, to be rescued not by youthful bravery, but by

the wisdom of a solitary old man; where the elusive waters of the

Spring of Immortality flow (II.39); where Alexander learns of his

untimely death at the oracle of Apollo in the City of the Sun (II.44);

and where dwell the Naked Philosophers—Brahmins living lives

of primitive simplicity, dedicated to the pursuit of wisdom—with

whom Alexander engages in a losing battle not of arms, but of

wits (III.5-6). This is a tale of the darkness of ignorance giving way

to the enlightenment of knowledge, of immortality and divinely

inspired wisdom that is only to be found beyond the bounds of

the known world.5

note the comments of P. Green, Alexander of Macedon 356-323 B.C.: A Historical

Biography (Berkeley/Los Angeles/London 21992) 411.

2

Green, Alexander of Macedon 409-410.

3

On the rise of the Alexander romantic tradition, see J. S. Romm, Edges of the

Earth in Ancient Thought: Geography, Exploration, and Fiction (Princeton 1992) 109-120.

4

Citations following R. Stoneman, The Greek Alexander Romance (London 1991).

5

And it is a tale that would be repeated and embellished by Philostratus in

his Life of Apollonius of Tyana. The hero, a latter-day Alexander in the form of a

mystic, succeeds in crossing that symbolic terminus, the Hyphasis, his experiences with the wonders of the east culminating in his interview with an Indian

�at the edge of the world

185

The Alexander tradition recasts history with a fantasy that

is invariably conjured up by thoughts of the ends of the earth.

Indeed, no region of the cosmos plays upon the imagination like

the horizon; seemingly approachable, but ever distant, it is the great

divide between day and night, between what is known and what

is unknown. It is a liminal space that for many cultures, as for the

Greeks, is removed from the laws that govern the natural world,

not subject to the constraints of space and time, a region populated

by fantastic creatures that can only exist beyond the map.

In Egypt this is the realm of Aker, guardian of the mountains of sunrise and sunset, the traditional points of access to the

Netherworld. As the manifestation of the polarity inherent to the

horizon, Aker is commonly depicted as two opposing lions or

sphinxes, who, facing west and east, bear the respective names Sef

and Tuau—‘yesterday’ and ‘today’—and look simultaneously to the

past and to the future.6 As the personification of the Netherworld,

more broadly, Aker was naturally associated with death, but also,

in accord with his twin nature, with the Netherworld’s regenerative

aspects, being closely connected to the Sun-god’s nightly journey

and rebirth at dawn.7

So, too, in Mesopotamia the edges of the earth are shrouded in

myth and it is the Sun-god who is master of this domain by virtue of

his daily journey: “To the distant stretches that are not known and

for uncounted leagues, Šamaš, you work ceaselessly going by day

and returning by night.”8 The Mesopotamian horizon—ki dUtu è(-a)

= ašar īt dŠamši “place of the rising Sun(-god)”9—is a region with its

philosopher-king, Iarchas. (Romm, Edges of the Earth 116-120; see also G. Anderson,

Philostratus: Biography and Belles Lettres in the Third Century A.D. [London/Sydney/

Dover, NH 1986]).

6

“Aker”, in Lexikon der Ägyptologie, vol. 1 (Weisbaden 1975) 114-115.

7

The primary sources for Aker are the New Kingdom Books of the Netherworld—

the Amduat, the Book of Caverns and the Book of Earth (Book of Aker), see E.

Hornung, Tal der Könige (Zurich/Munich 1982); idem, Altägyptische Jenseitbücher

(Darmstadt 1997).

8

Ϟaϟ-na šid-di šá la i-di ni-su-ti u bi-ri la ma-n[u-ti ] dŠamaš dal-pa-ta šá ur-ra tal-li-ka

u mu-šá ta-sa -r[a] (BWL 128: 43-44).

9

E.g., KAR 46: 15-16. As will be clear from the evidence presented below, the

expression also occurs with kur/šadû, i.e., “mountain of sunrise/sunset.” On the

Sumerian genitival compound as well as writings without the divine determinative,

see J. Polonsky, “ki-dutu-è-a: Where Destiny is Determined”, Landscapes: Territories,

Frontiers and Horizons in the Ancient Near East, Part III: Landscape in Ideology, Religion,

Literature and Art (HANE Monographs III/3, CRAI 44; Padova 2000) 90 nn. 8-9,

with previous literature.

�186

christopher woods

own iconography and imagery, with a cosmography that straddles

reality and myth. As in the Egyptian conception, it is the gateway

to the Netherworld, the womb of the future, the point where the

Sun-god emerges into the heavens bringing to fruition the coming

day. It is at daybreak that fates are determined and judgments are

decided on the horizon. This is the moment of manifestation—[ìne]-éš dUtu è-a ur5!(GÌRI) hé-en-na-nam “Now, as the Sun rises, it

is indeed so,” to quote a popular Sumerian turn of phrase.10 And,

like its Greek counterpart—with which it has so much in common

and with which comparisons are inevitable—the Mesopotamian

horizon is intimately bound up with heavenly wisdom, immortality,

and creation, from cosmogony to birth.

Of Animals, Trees, and Insects:

The Iconography of the Eastern Horizon

The path of the sun defines the limits of the Mesopotamian world,

d

Utu è-ta dUtu šú-a-šè/ištu īt dŠamši adi ereb dŠamši “from sunrise

to sunset.”11 In the cosmological conception, in its broadest terms,

the Sun-god, Utu-Šamaš, scales the eastern mountains in his daily

ascent and emerges through the gates of heaven in a thunderous

event that ushers in a new day. Cosmography clearly mimics geography, bound as Mesopotamia is to the east and southeast by the

southern course of the Zagros. And as the Taurus and Amanus

provide a northwestern perimeter, the mountain of sunrise has a

cosmic counterpart to the west, the mountain of sunset.12 But these

10

A Mythic Narrative about Inana 45; this is a unique morphological variant

of an expression usually written dUtu ud-dè(-e)-a (see Cooper Curse of Agade 257

ad 272; B. Brown and G. Zólyomi, Iraq 63 [2001] 151 and nn. 17-18).

11

SBH 47: 19-20. Other idioms referring to the horizon include zag-an-na

(an-zag [ pā šamê, šaplan šamê ]) ‘edge/lower parts of heaven’, zag-ki(-a) ‘border of

earth’, an-šár ‘entirety of heaven’, ki-šár ‘entirety of earth’, an-úr (išid šamê) ‘foundation of heaven’, as well as kippat mātāti ‘circle of the lands’, kippat er eti ‘circle of

earth’, kippat tubuqāt erbetti ‘circle of the four corners’, kippat šār erbetti ‘circle of the

four (regions)’—see W. Horowitz, Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography (MC 8; Winona

Lake, IN 1998) 234-236, 330-334.

12

Occassionally, the horizon is defined in terms of the mountains of sunrise

and sunset, e.g., sig-šè igi mu-íl an-ùn-na kur dUtu è-ke4-ne igi bí-du8 nim-šè igi

mu-íl an-ùn-na kur dUtu šú-ke4-ne igi bí-du8 “(Šukaletuda) looked down(river [i.e.,

east]) and saw the heavens of the land where the sun rises. He looked up(river

[i.e., west]) and saw the heavens of the land where the sun sets” (Inana and

Šukaletuda 149-150; also 101-102, 271-272; see Horowitz, Cosmic Geography 249);

d

Utu è-a-ta kur dUtu šú-a-šè “from the mountain of sunrise to the mountain of

�at the edge of the world

187

are symbolic, mythical locations as sunrise and sunset vary by nearly

56º during the course of the year. From the perspective of southern

Mesopotamia, the sun rises over the central Zagros at the summer

solstice, migrating south until it rises over the Persian Gulf at the

winter solstice.13 Little is known of the mountain of sunset. Udughul

identifies the Dark Mountain (hur-sag/kur gi6-ga), the mountain of

sunset, as the remote birthplace of seven demons who were subsequently reared on the Bright Mountain (hur-sag/kur babbar-ra),

the mountain of sunrise.14 Elsewhere, there is mention of a Mt.

Buduhudug that carries the epithet nēreb dŠamaš <ana> dAya “the

entrance of Šamaš to Aya,”15 and so too must be a name for the

mountain of sunset since it is upon his return to the Netherworld

that the Sun-god is reunited each night with his spouse.16

As in other cultures, there is a natural association in Mesopotamia

between the west, the sun’s failing light, and death. Nergal and

Ereškigal are master and mistress of the realm of the setting sun,

bearing the respective epithets lugal ud šú and nin ki ud šu4.17

Incantations that compel ghosts to return to the Netherworld do

so by commanding them to travel west, to the place of sunset,18

while figurines of ghosts ritually expelled from homes were buried

sunset”—referring to the extent of Enlil’s domain (CT 42, 39 [85204] 26; ed.

Cohen Lamentations 339-341).

13

See B. Alster, “Dilmun, Bahrain, and the Alleged Paradise in Sumerian Myth

and Literature”, in: D. T. Potts, Dilmun: New Studies in the Archaelogy and Early History

of Bahrain (BBVO 2; Berlin 1983) 45.

14

von Weiher Uruk 1 ii 2-5, 16-19; CT 16 44: 84-87, 98-101—see M. J.

Geller, Evil Demons: Canonical Utukkū Lemnūtu Incantations (SAACT 5, Helsinki 2007)

167: 46-47; cf. KAR 24: 5-7—see George, Gilgamesh 493 n. 169, with previous

literature. For further attestations of ki (d)Utu-šú, see Polonsky, “Rise of the Sun

God” 275-276 n. 824.

15

MSL 11, 23: 5//von Weiher Uruk 114 i 5 (Hh.)—see George, Gilgamesh

863 ad 38-39, for discussion, previous literature, and duplicates. Further, note

the equation hur-sag dUtu-šú-a-šè : ana šadî ereb dŠamši (Udughul IV 61)—cited

in ibid. 864.

16

See M.-J. Seux, Hymnes et prières aux dieux de babylonie et d’assyrie (Paris

1976) 215-216; W. Heimpel, “The Sun at Night and the Doors of Heaven in

Babylonian Texts”, JCS 38 (1986) 129.

17

Nergal: Temple Hymns 44: 464 (cf. dLugal sur7(KI.GAG) šú-a “lord who

descends into the pit” [CT 25, 35 rev. 10; 36 rev. 16; 37: 12—see Tallqvist

Götterepitheta 355; Temple Hymns 136]); Ereškigal: Steible NBW 2, 343: 2;

344: 2—šu4 is syllabic for šú.

18

E.g., ana ereb dŠamši lillik ana dBidu Ì.DU8.GAL ša er etim lū paqid “May he

(i.e., the ghost) go to where the sun sets, may he be placed in the charge of Bidu,

the chief-gatekeeper of the Netherworld” ( J. A. Scurlock, “KAR 267//BMS 53:

A Ghostly Light on bīt rimki?”, JAOS 108 [1988] 206: 18-20; see also George,

Gilgamesh 500 n. 192).

�188

christopher woods

at sunset, often facing west.19 And, of course, the Sun-god’s descent

beyond the western horizon is intimately connected with the judging of the dead in the Netherworld at night.20

But it was the more auspicious eastern horizon with its promise

of a new day that captivated the Mesopotamian imagination, a

preoccupation that is reflected in the choice of the Sun-god’s spouse,

Aya-Šerida—Dawn. Just before sunrise, gatekeepers21 thrust open

the gates to the heavens in anticipation of the Sun-god’s ascent.

In text, the sun’s youth at dawn is epitomized by the epithet šul

d

Utu “young man Utu” and his daily ascent into the azure heavens

is portrayed as a series of images in lapis lazuli: ascending a lapis

stairway, bearing a lapis staff, sitting upon a lapis dais, or donning

a lapis beard that, in one instance, is described as “dewy,”22 a

particularly striking image of dawn. These are the symbols of the

night sky just prior to daybreak, fixed epithets not unlike Homer’s

“Rosy-fingered dawn,” “Dawn the saffron-robed” and, notably, the

purple steeds of Ushas, Dawn, in the Rig Veda.23 In one of the most

recognizable scenes from the glyptic of the Sargonic period, Šamaš

19

J. A. Scurlock, “K 164 (BA 2, P. 635): New Light on the Mourning Rites for

Dumuzi?”, RA 86 (1992) 64, who further points out that apotropaic figurines, on

the other hand, faced east and were consecrated at sunrise; discussed by M. Huxley,

“The gates and guardians in Sennacherib’s addition to the temple of Assur”, Iraq

62 (2000) 110-111 and n. 6.

20

See Heimpel, JCS 38, 148.

21

Described as “(the two) guards of heaven and the Netherworld” in the

Elevation of Ištar: [dimmer min-na]-bi en-nu-un an-ki-a giš ig-an-na gál-la-ar

d

Nanna dUtu-ra gi6gi ud-da šu-ta-ta an-ni-ši-íb-si : ana DINGIR.MEŠ ki-lal-la-an

ma-a - ar AN-e u KI-tim pe-tu-ú da-lat dA-nu ana d30 u dUTU u4-mu u mu-ši ma-alma-liš ba-šim-ma “For the two gods, the guards of heaven and the Netherworld,

the ones who open the gates of An, for Sin and Šamaš, the day and night are

divided equally” (TCL 6, 51 rev. 1-4; ed. B. Hruška, ArOr 37 [1969] 473-522); cf.

the two protomes that manipulate the solar disk on the Nabû-apla-iddina tablet

(BBSt., pl. 98 [no. 36]).

22

su6-na4za-gìn-duru5-e lá (Temple Hymns 27: 173; cf. 87 ad 173). References

to simmilat uqnîm ‘lapis staircase’, šibirri uqnîm ‘lapis scepter’, barag-za-gìn-na ‘lapis

dais’, and su6-na4za-gìn ‘lapis beard’ are collected and discussed by Polonsky, “Rise

of the Sun God” 192-193, 196.

23

Note also the phrase an-za-gìn ‘lapis heavens’ discussed by Horowitz, Cosmic

Geography 166-168, where the author further observes that Nisaba’s ‘Tablet of

the Stars of Heaven’ (dub-mul-an) is made of lapis lazuli. Further, referring to

the nether sky, note: dUtu an za-gìn-ta è-a “Utu, who comes forth from the lapis

heavens” (Incantation to Utu 1; ed. B. Alster, ASJ 13 [1991] 37)—the cosmic

identity between the Netherworld sky and the night sky is discussed below.

On the metaphorical uses of lapis lazuli more generally, see I. J. Winter, “The

Aesthetic Value of Lapis Lazuli in Mesopotamia”, in: Cornaline et pierres précieuses:

la Méditerranée, de l’Antiquité à l’Islam (Paris 1999) 43-58.

�at the edge of the world

189

rises between the two peaks brandishing his distinctive šaššaru-saw.

In some scenes lions atop the eaves serve as visual metaphors for

this thunderous event,24 an image that is but one facet of a broader

motif that contrasts the stillness and silent anticipation that night

engenders with the bustle and clamor that announces a new day:

“When dawn was breaking, when the horizon became bright, when

the birds began to sing at the break of day, when Utu emerged

from his cella . . .”25

In yet other seals, the setting of this scene is couched in the

symbolic code of a subtler iconographic language. In figs. 1 and 2,

two opposed recumbent bison replace the peaks of the mountain

of sunrise. As the logogram for kusarikkum bears witness, i.e., GUD.

DUMU.dUTU ‘Bison-Son-of-the-Sun-god’, bison, and with them

the mythical bison-men, enjoy an intimate association with the

Sun-god, being indigenous to the hilly flanks of the Zagros where

the sun rises.26 Indeed, it is this aspect of the natural history of the

east that accounts for the bellowing roar with which daybreak was

associated, as well as the bovine epithets of the Sun-god that include

gud, gud-alim, and am: ur-sag gud ha-šu-úr-ta è-a gù huš dé-dé-e

šul dUtu gud silim-ma gub-ba ù-na silig gar-ra “hero, bull rising

from (Mt.) Hašur, bellowing truculently, the youth Utu, the bull

standing triumphantly, audaciously, majestically.”27 Of a different

type is the visual gloss of location that appears in figs. 3 and 4—a

E.g., R. M. Boehmer, Die Entwicklung der Glyptik während der Akkad-Zeit (UAVA

4; Berlin 1965) Abb. 409, 420.

25

ud zal-le-da an-úr zalag-ge-da buru5 ud zal-le šeg10 gi4-gi4-da dUtu agrun-ta

è-a-ni . . . (Gilgameš, Enkidu, and the Netherworld 47-49; similarly, 91-93). Also

note, among many other possible examples: ud-ba lugal-mu è-da-ni-ne an muϞunϟ-da-Ϟdúbϟ-dúb ki mu-un-da-Ϟsìgϟ-[sìg] “as my king (Utu) comes forth, the

heavens tremble before him and the earth shakes before him” (Hymn to Utu B

13-14); en dumu dNin-gal-la . . . ud-gim kur-ra gù Ϟmuϟ-[ni]-ib-bé “the lord (Utu),

the son of Ningal . . . thunders over the mountains like a storm (27-28); mušen-e

á ud zal-le-da-ka ní un-gíd Anzumušen-dè dUtu è-a-ra šeg11 un-gi4 šeg11 gi4-bi-šè

kur-ra Lu5-lu5-bi-a ki mu-un-ra-ra-ra “when at daybreak the bird stretches his

wings, when at sunrise Anzu cries out, at his cry the earth in the Lulubi mountain

quakes” (Lugalbanda 44-45).

26

Wiggermann Protective Spirits 174; on these two seals (figs. 1 and 2), see

also P. Steinkeller, “Early Semitic Literature and Third Millennium Seals with

Mythological Motifs”, Quaderni di Semitistica 18 (1992) 266, pl. 8 nos. 5 and 6.

27

Enki and the World Order 374-375. The association between the Sun-god

and the bison is attested already in the ED Šamaš literary text, ARET 5, 6//IAS

326+342: na-mu-ra-tum dUTU GABA HUR.SAG i-gú-ul “the radiance of Šamaš

‘ate’ (his) wild bull(s) in front of the mountain” (following M. Krebernik, Quaderni

di Semitistica 18, 76: C6.6).

24

�190

christopher woods

large horn atop a mountain that the Sun-god, or perhaps Moongod, scales. Quite likely, it belongs to the wild or Bezoar goat, Capra

aegagrus, a species that is recognized for its majestic recurved horns

and is also native to the slopes of the Zagros.28 Thus, like the bison,

the Bezoar goat serves as a visual metonym for the mountainous

eastern horizon, a claim that finds support in fig. 5 where two wild

goats are depicted flanking a rising Sun-god.

Flora also play a part in this iconography. A number of scenes of

the rising Sun-god incorporate a particular conical tree (figs. 6-10).

Its shape suggests a conifer of some type, although the occasional

addition of an apex of three off-shoots may imply further, mythical

influences (figs. 11-12). Likely, the tree of the seals is to be connected to the hašur/ ašurru-tree of text, a tree so closely associated

with the rising Sun-god that it lends its name to the mountain of

sunrise in literary sources: “Utu, as you emerge from the pure

nether heavens, as you pass over Mt. Hašur . . . ”29 Identification of

the hašur-tree is somewhat facilitated by the fact that few coniferous trees are indigenous to the central and southern stretches of

the Zagros. One likely candidate, which accords well with the

depictions in text and art, is the stately Indian Juniper, Juniperus

polycarpos, a tall, upright-growing conifer that climbs high along the

slopes of the Zagros.30

28

See already the comments of Boehmer, Die Entwicklung 73. On the identification with the Moon-god, see E. A. Braun-Holzinger, “Die Ikonographie des

Mondgottes in der Glyptik des III. Jahrtausends v.Chr.”, ZA 83 (1993) 119-135.

29 d

Utu an šag4 kug-ga-ta e-ti-a-zu-de3 kur ha-šur-ra-ta b[a]la-dè-zu-dè : dUTU

ul-tu AN-e KUG.MEŠ ina a- e-ka šá-du-u a-š[u]r ina na-bal-kut-ti-ka (Akk.: “pure

heavens;” T. J. Meek, BA 10/1, 66 and 68: 11-14; ed. ibid., p. 1—discussed by

Heimpel, JCS 38, 143; George, Gilgamesh 864). Regarding Sum. an šag4, see the

discussion of šag4-an-na below. Further, note: dUtu ha-šu-úr-ta Ϟèϟ-[àm] “(Ninurta)

like Utu who came forth from the (Mt.) ašur . . .” (Ninurta A, Segment A 13);

gud gišeren duru5 nag-a ha-[šu]-úr-Ϟra pešϟ-a “(Utu) bull who drinks among the

dewy eren-trees, which grow on (Mt.) Hašur” (Utu Hymn B 10); šul dUtu en kur!

giš

ha-šu-úr-ra “Youth, Utu, lord of Mt. ašur” (VAS 2, 73: 12); see also Enki and

the World Order 374-375 (quoted above) and Lugalbanda and the Mountain

Cave 228-229 (quoted n. 123).

30

Note the diverging definitions of the CAD

sub ašurru ‘(a kind of cedar)’

and AHw. sub ašūrum, ašurru ‘eine Zypressenart’. According to M. Zohary,

Juniperus polycarpos grows to a height of 20 m. and climbs to an altitude of 2,700 m.

(Geobotanical Foundations of the Middle East, 2 vols. [Stuttgart/Amsterdam 1973] 351;

352 fig. 141 a [distribution]; 585 fig. 251 [photo]). J. Hansman, “Gilgamesh,

Humbaba and the Land of the Erin-Trees”, Iraq 38 (1976) 29 refers to this tree

as Juniperus excelsa, the so-called Greek juniper, a tree so closely related to Juniperus

polycarpos that some botanists consider the two identical (Zohary, Geobotanical

�at the edge of the world

191

This same tree, Juniperus polycarpos, has been identified by Klein

and Abraham as the referent of the Zagros-growing gišeren in

Gilgameš and Huwawa.31 Indeed, in addition to the designation

kur hašur, the mountain of sunrise is also, although less frequently,

referred to as kur (šim) gišeren(-na) “mountain of (fragrant) erentrees,” e.g., dUtu kur šim gišeren-na-ta è-a-ni “as Utu rises from the

mountain of fragrant eren-trees.”32 But, as has long been recognized,

cedars, the generally accepted identification of gišeren, do not grow

on the southern stretch of the Zagros, a problem that arises most

frequently in the context of reconciling Gilgameš’s eastward journey to the eren-mountains in Gilgameš and Huwawa with his less

problematic travels to the Lebanese erēnu-forest in the later Akkadian

epic.33 A number of solutions have been proposed for this problem

of historical geography, including Bottéro’s understanding of eren

as, in origin, a generic term for any resinous or coniferous tree.34

If this is the case, there may have been no rigorous distinction, at

least in early texts, between the broad designation eren and the narrower term hašur, a term that, presumably, referred particularly to

those conifers that grow on the slopes of the southern Zagros, i.e.,

Juniperos polycarpos. With Mesopotamian classifications often being

based on vague semantic associations without unique correspondences between object and label, it is quite conceivable that the two

terms were used interchangeably to refer to the same tree.35

Having invoked Gilgameš, we cannot overlook that most famous of

encounters to take place at the ends of the earth: upon approaching

Foundations 351); M. B. Rowton, “The Woodlands of Ancient Western Asia”,

JNES 26 (1967) 268 identified the hašur-tree with the Mediterranean cypress,

Cupressus sempervirens horizontalis, and Mt. Hašur with the Eastern Taurus. See

also the comments of J. Klein and K. Abraham, “Problems of Geography in the

Gilgameš Epics: The Journey to the ‘Cedar Forest’ ”, Landscapes: Territories, Frontiers

and Horizons in the Ancient Near East, Part III: Landscape in Ideology, Religion, Literature

and Art (HANE Monographs III/3, CRAI 44; Padova 2000) 66.

31

Klein and Abraham, CRAI 44, 66.

32

Inana E 27. For further attestations, see Heimpel, JCS 38, 144; Polonsky,

“The Rise of the Sun God” 306-327.

33

Klein and Abraham, CRAI 44, 65-66, with previous literature.

34

J. Bottéro, L’épopée de Gilgameš (Paris 1992) 28 n. 2.

35

Note, in this connection, the tradition preserved in the Incantation to Utu

where the opposition implies that kur eren refers to the mountain of sunset, and

kur hašur to the mountain of sunrise: dUtu a-ab-ba igi-nim za-a-kam dUtu a-abba igi-sig za-a-kam dUtu kur eren-na kur ha-šu-ra za-a-kam “Utu, the upper sea

is yours, Utu, the lower sea is yours, Utu, Mt. Eren (and) Mt. Hašur are yours”

(Alster, ASJ 13, 43: 33-35); cf. Hymn to Utu B 10, cited above in n. 29.

�192

christopher woods

the gates of sunrise on Mt. Māšu—the “Twin Mountain,” recalling

the dual mountain peaks of the glyptic—Gilgameš finds the way

barred by a scorpion-man and scorpion-woman, who together

“guard the sun at sunrise and sunset” (IX 45).36 But the scorpion’s

association with the Sun-god is not limited to the epic. In the glyptic scorpion-men are often attested manipulating, or otherwise in

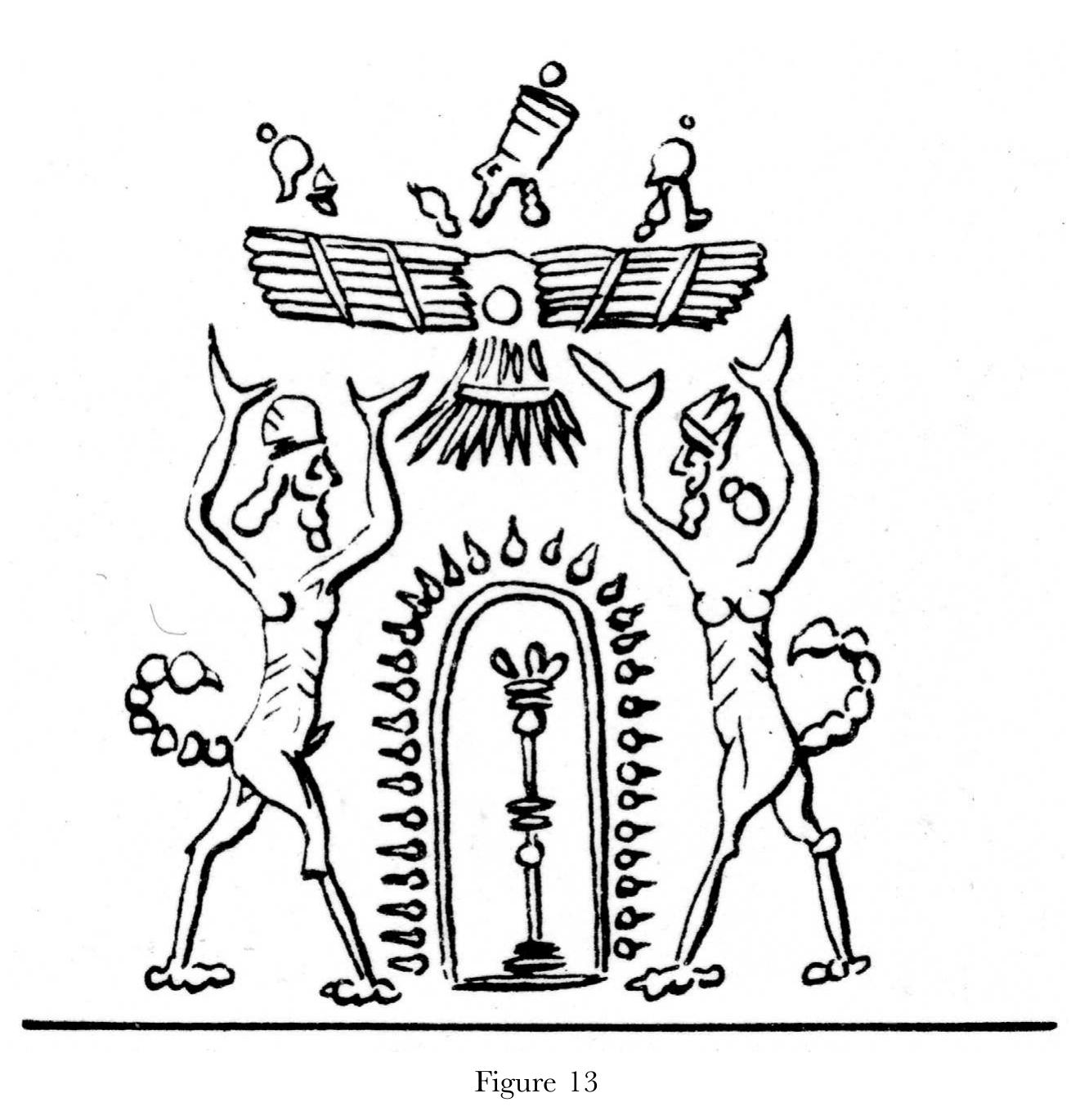

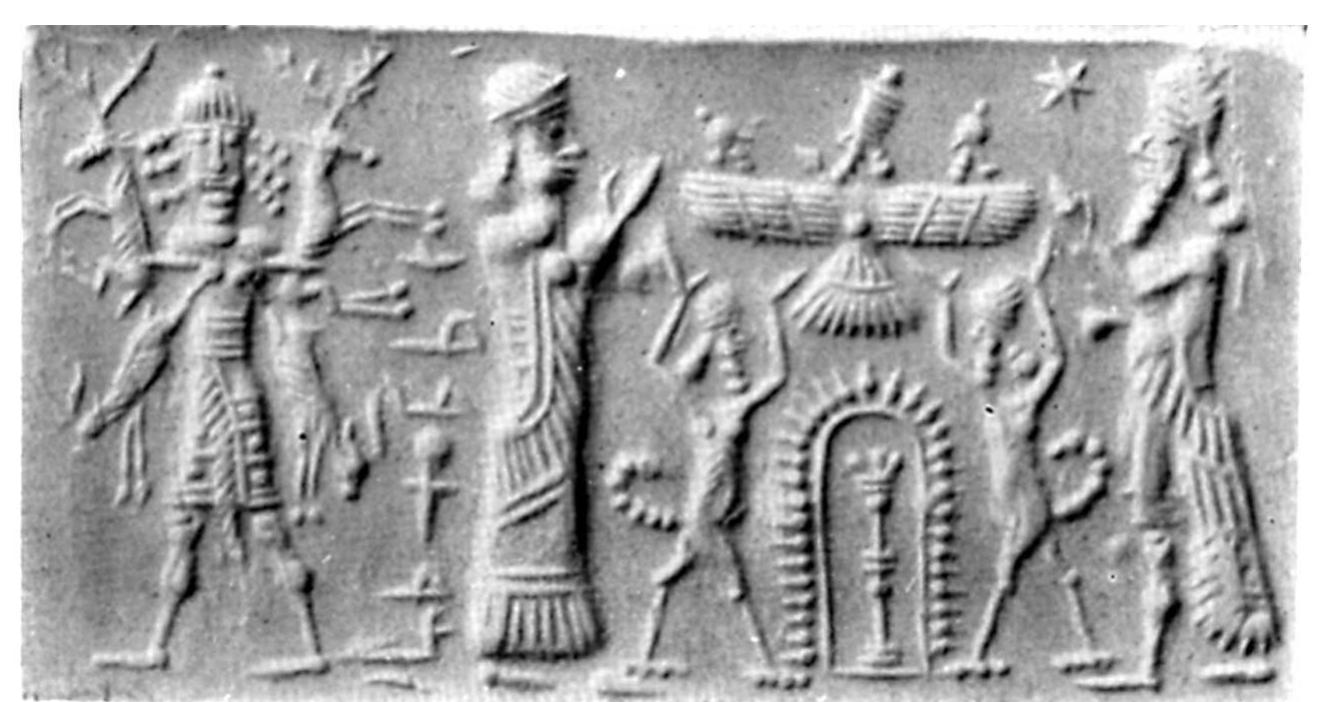

association with, the winged solar disk (figs. 13-20).37 Nor is this

an innovation of the first millennium. It is an old pairing, having

roots that go at least as deep as the third millennium: in fig. 21

the ray-bedecked god is likely Utu-Šamaš, who is assisted by a

scorpion-man in combat, and in fig. 22 a scorpion appears in the

so-called ‘Sun-god in his boat’ motif. Corroboration is to be found

in fig. 23, where the image is bordered by a scorpion that, with

pincers raised towards heaven, supports the Sun-god wielding his

šaššaru-saw; in fig. 24 an identically portrayed scorpion appears

beneath a star, the image serving as a border motif for a scene of

the Sun-god rising. Finally, in fig. 25, an OB seal in which text

comes together with image, a scorpion appears below a legend

bearing the inscription dUTU dA-a.

Surely there is some underlying significance to the association

of the Sun-god, the horizon, and the scorpion as there is with the

bison, the wild goat, and the juniper tree. As with Janus-faced Aker,

who looks to both day and night, the explanation lies in a polarity

that both the horizon and the scorpion embrace. The horizon is the

line separating life from death, and is, therefore, defined by both.

On the far side are night, the Netherworld, and so death; on the

near side are day, the reborn sun, and the promise of life.38 The

scorpion is an obvious symbol of death and night. A stealthy and

36

A curious parallel presents itself in the Alexander tradition, where scorpions

are similarly associated with the distant east. In the so-called Letter to Aristotle,

Alexander writes of swarms of scorpions overcoming the Macedonian army while

bivouacking in India, one of several unfortunate incidents during the Night of

Terrors (Romm, Edges of the Earth 114).

37

The relationship between the Sun-god and the Scorpion-man in the first

millennium is discussed by Huxley, Iraq 62, 120-123.

38

The duality of the horizon, embracing both night and day, explains the

ostensibly contradictory lexical tradition which equates ganzir, the gate of the

Netherworld (and so necessarily lying on the horizon) not only with kukkû ‘darkness’, but also with nablum ‘flame’ (see CAD K sub kukkû lex.; N/1 sub nablu lex.);

cf. R. Borger, AOAT 1, 11; idem, WO 5 (1969-1970) 172-173; and W. R. Sladek,

“Inanna’s Descent to the Netherworld” (The Johns Hopkins University, Ph.D.

1974) 59-61. As discussed further below, the equation with nablum is likely based

on the understanding that the sun bursts into flame at daybreak.

�at the edge of the world

193

deadly predator, the scorpion is a nocturnal creature that lives in

the crevices of the earth. Indeed, it was likely this Netherworldly,

chthonic quality,39 along with the scorpion’s long-standing relationship with the Sun-god, that earned the goddess Iš ara—symbolized

first by the serpent (bašmu) and then the scorpion, and represented

by the constellation Scorpio—the epithets wāšibat kummim “one

who dwells in the (Netherworld) residence (of the Sun-god)” and,

in connection with the Sun-god’s Netherworld activities, bēlet dīnim

u bīrim “lady of judgment and divination.”40

But, paradoxically, the scorpion is, like the eastern horizon, also

a symbol of life and rebirth. As a snake sheds its skin—an act heavy

with symbolism—the scorpion regularly undergoes ecdysis or molting, casting off its exoskeleton and emerging substantially larger

than before. Thus, as in other cultures, it is the natural biology of

the scorpion that makes it a symbol of birth and rejuvenation in

Mesopotamia. Indeed, it is this rejuvenative aspect that sheds light

upon Iš ara’s role as a goddess of sex, for when Gilgameš exercises

his prerogative of ius primae noctis he does so on “the bed that was

laid out for Iš ara”41—a statement from the epic that is corroborated in text by the goddess’s epithet bēlet râme “lady of love”42

39

This association is already hinted at in Ur III offering texts in which Iš ara

is connected with Allatum among other chthonic deities, e.g., AUCT 2, 97 iii

43f.; see D. Prechel, Die Göttin Iš ara. Ein Beitrag zur altorientalischen Religionsgeschichte

(ASPM 11; Münster 1996) 26-31, 188.

40

YOS 11, 23 i 14 and BBR 87 i 6 respectively. In An = Anum III 281-282

Iš ara is counted among the entourage of Šamaš and Adad, while in I 201 and

IV 277 she bears the title bēlet bīri “lady of divination.” On these epithets, as well

as the relationship between divination and the Netherworld more broadly, see

now Steinkeller, Biblica et Orientalia 48, 11-47. A close association with Šamaš

is suggested already for the OB period by the fact that the šaššarum of Šamaš and

the bašmum of Iš ara were together employed in oaths, e.g., ŠU.NIR ša dUTU

ša-ša-rum ša dUTU ba-aš-mu-um ša Eš- ar-ra a-na ga-gi-im i-ru-bu-ma “the emblem

of Šamaš, the saw of Šamaš, the snake of Iš ara came into the gagûm” (CT 2, 47:

18—rev. 1; see Prechel, Die Göttin Iš ara 39).

41

a-na dIš- a-ra ma-a-a-lum na-Ϟdiϟ-i-ma (Gilg. P v 196-197; George, Gilgamesh

178-179).

42

LKA 102: 12; ed. Biggs Šaziga 6. Note the early association of the scorpion

as a symbol of the sex act in the Barton Cylinder ii 11-12; ed. B. Alster and

A. Westenholz, “The Barton Cylinder,” ASJ 16 [1994] 15-46. The scorpion, as

representative of both life and death is captured in the Nugal Hymn, where the

gate of the Nungal’s prison—which, as discussed below, is paradoxically symbolic

of both the Netherworld and the womb—is described as decorated with, or having

the form of, a scorpion, i.e., a-sal-bar-bi gíri sahar-ta ím-ma ka ša-an-ša5-ša5-dam

‘its architrave? is a scorpion that quickly dashes from the dust, overpowering (all)’

(Nungal Hymn 16).

�194

christopher woods

and in image by the inclusion of scorpions in scenes that depict

the nuptial bed (figs. 26-27). A possible derivation of the goddess’s

name from the root š r ‘dawn’43 would show a regenerative solar

aspect to be fundamental to her character, while an association

with the horizon itself is made plain by her name dÍb-Du6-kug-ga

‘Fury of the Dukug’;44 as will be discussed below, Dukug, the bond

of the Upper- and Netherworld, is the location par excellence of the

eastern horizon. Furthermore, it is the scorpion’s connection with

reproduction that accounts for the presence of a pair of scorpionpeople—of opposite sex—on Mt. Māšu, a conception that is also

embedded in a Neo-Assyrian ritual that prescribes the fashioning

of a large number of pairs of prophylactic figurines; however, only

for the girtablullû does it call for the manufacture of one male and

one female.45 Finally, we should not overlook one aspect of the

natural biology of scorpions that speaks tellingly to this symbolic

duality, namely, their cannibalistic mating practices of which the

ancients may well have been aware—after a complicated mating

ritual, coitus very often ends46 with the female killing the male, so

uniting death with the reproductive act itself.

The Babylonian oikoumenē ‘Known World’, Immortality,

and the Path of the Sun

A horizon dominated to the east and west by the mountains of sunrise and sunset is the most common conception of the edges of the

earth in Mesopotamian sources. But it is not the only one. Gilgameš

IX-X describes regions beyond Mt. Māšu: the Path of the Sun ( arrān

Šamši ), where, in fact, the sun does not shine, the gemstone garden,

the cosmic sea (tâmtu) and the waters of death (mê mûti ), and, across

these waters, the realm of Ūta-napišti at pî nārāti “the mouth of

the rivers.” These far reaches, as Šiduri admonishes Gilgameš, are

the exclusive domain of the Sun-god: “Never, Gilgameš, has there

ever been a crossing, and anyone who has come since the dawn of

time has not been able to cross the sea. The crosser of the sea is

See W. G. Lambert, “Iš ara”, RlA 5 [1976-1980] 176.

An = Anum I 199.

45

Wiggermann Protective Spirits 14-15: 186-187, 52 (comm.).

46

Specifically, in nearly 40% of all cases by some estimates—see G. A. Polis

and W. D. Sissom, “Life History”, in: G. A. Polis, The Biology of Scorpions (Stanford

1990) 161-172.

43

44

�at the edge of the world

195

valiant Šamaš, other than Šamaš, who can cross?”47 This same sea,

bearing the designation ídMarratu, is portrayed on the Babylonian

Map of the World as beyond the mountains of sunrise and sunset,

a cosmic river encircling the earth.48 What is at issue here is not,

necessarily, an inherent contradiction in our sources, or evidence

for an evolving tradition, as suggested elsewhere,49 but the mental

map as conceived from different perspectives.

For the Greeks the world consisted of two parts. There was the

oikoumenē, the “known or familiar world”—“our world”—which,

according to Romm, “constitutes the space within which empirical

investigation . . . can take place, since all of its regions fall within

the compass either of travel or of informed report.”50 And there

are the unfamiliar regions beyond the oikoumenē, lands of which

little or nothing was commonly known and which, therefore, lent

themselves to myth and fantasy. Much like the Greek notion of

the oikoumenē, the mountains of sunrise and sunset define the limit

of the Mesopotamian known world. Cosmography is shaped by

topography, with the Zagros, in particular, providing not only

a considerable physical barrier, but bounding Mesopotamian

culture as well, defining, in essence, the eastern horizon of the

Mesopotamian “our world.” Like the Greek conception and maps

of old that detail empirical geography, but assign the distant regions

beyond exploration to the realm of fantasy—hic sunt dracones “Here

be dragons”—the Mesopotamian world consists of the known and

47

Gilg. X 79-82. This admonition is not unlike the legendary council given to

Alexander when the conqueror dares to speak of crossing unfathomable Ocean:

“This is not the Euphrates nor Indus, but whether it is the endpoint of the land,

or the boundary of nature, or the most ancient of elements, or the origin of the

gods, its water is too holy to be crossed by ships” (A Greek epigram collected by

Seneca the Elder in his Suasoriae; following Romm, Edges of the Earth 25-26).

48

For the Babylonian Map of the World, see Horowitz, Cosmic Geography 20-42;

although not specifically labeled as the mountains of sunrise and sunset, this identification is suggested by the fact the limits of the continental earth were conceived

as bordered by mountains (see Horowitz, Cosmic Geography, 331-332).

49

See Horowitz, Cosmic Geography 330. George, Gilgamesh 496-497, attributes this

apparent discrepancy to a historical development in which an older cosmography

that viewed the Zagros as the eastern horizon was replaced by a later view, based

on empirical investigation, that knew of lands beyond the mountains. This solution,

however, runs afoul of the fact that those who expressed the “older” tradition

(e.g., the scenes of the Sun-god rising of Sargonic glyptic and OB references to

the Sun-god emerging from Mt. Hašur) were well aware of regions beyond the

Zagros, such as Elam and Melu a—indeed, they had greater contacts with the

peoples beyond the Zagros than did their later counterparts.

50

Romm, Edges of the Earth 37.

�196

christopher woods

the unknown. Akkadian scenes of the Sun-god rising and references

to the Sun-god rising from Mt. Hašur, all seeming to imply a world

with a mountainous perimeter, focus upon the more mundane

limits of the familiar world, the eastern horizon as viewed from

the perspective of the Babylonian oikoumenē. The conception of the

edges of the world captured in Gilgameš and the Babylonian Map

of the World is broader and more ambitious, incorporating the

mythical terra incognita that lay beyond the mountains of sunrise and

sunset, the cosmic counterpart of the lesser-known and foreign lands

beyond the Zagros. More than a contradiction, it is an expansion

of the former notion.

It is in this light that we must revisit the much-discussed cosmography of the Path of the Sun and the regions beyond described

in Gilgameš IX-X. Most commentators have emended IX 39 so

that Gilgameš’s interview with the scorpion-people takes place on

the western horizon, at the mountain of sunset, rather than the

mountain of sunrise; Gilgameš’s journey to Ūta-napišti would then

proceed from west to east via what many assume to be a tunnel

though the Netherworld.51 But there is no compelling reason for the

emendation, no explicit mention of a tunnel, and no reference to

the Netherworld in the extant text.52 Nor is it necessary to subject the

claim that the scorpion-people, from Mt. Māšu, ana a ê Šamši u ereb

Šamši ina arū Šamšīma ‘guard the sun at sunrise and sunset’ (IX 45),

to an interpretation beyond what the text explicitly states.53 What is

often missed—and what is the source of much confusion regarding

this and the following passages—is that this mythical region, for

which Mt. Māšu serves as gateway, represents a purposeful paradox,

a place defined by diametrical opposition. It is a region where trees

of precious stone bear fruit of jewels (IX 171-194), where sailors

of stone navigate the Waters of Death, where a mortal man lives

in immortality, where an alewife, contrary to the expectations of

her profession, dons the veil (X 1-4), where the guardians consist

of a male-female pair, half human half animal (IX 37-51), the

latter represented by the scorpion, which, as previously discussed,

is symbolic of both life and death. And it is a region, where, at

See George, Gilgamesh 492-497, for a review of the previous literature discussing this and other interpretations of the Path of the Sun.

52

On this point, see also George, Gilgamesh 494.

53

Cf. George, Gilgamesh 492-493; Huxley, Iraq 62, 124-125; eadem, “The Shape

of the Cosmos According to Cuneiform Sources”, JRAS ns 7 (1997) 193.

51

�at the edge of the world

197

Mt. Māšu (again, “Twin Mountain,” the name itself expressing the

notion of duality) the sun both rises and sets (IX 45). At issue is the

phenomenon of coincidentia oppositorum, a cross-culturally observed

mythological theme in which the paradox of divine and mythical

reality is conceptualized as a union, and thereby transcendence,

of contraries.54 The horizon—itself a paradox, a liminal space, a

point of convergence between diametrical opposites—naturally lends

itself to such a conception.55 Parallels are encountered in Classical

sources. There are the Homeric Aithiopes, for instance, who are

split in two, some residing at sunrise and some at sunset (Odyssey

i 23-24), and, of particular interest in light of the description of

Mt. Māšu, is the Hesiodic Tartaros, where it is claimed that the

sun both rises and sets (Theogony 746-751).56

The passage detailing Gilgameš’s journey is unfortunately broken,

and so any interpretation is necessarily speculative. However, as

pointed out by George, it clearly concerns a race against the sun,

taking place, apparently, over 12 double-hours, that is, a whole day.57

I contend that Gilgameš’s journey begins in the east, at Mt. Māšu,

54

See, in particular, M. Eliade, Patterns in Comparative Religion. Trans. Rosemary

Sheed (Lincoln, NE/London 1996; originally published 1958 by Sheed & Ward,

Inc. New York) 419-424.

55

The duality and coincidence of opposites that is implicit to the horizon makes,

naturally, for a symbolic topos in literarature. For instance, Lugalbanda’s liminal

state between life and death is described in terms of the rising and setting of the

sun, e.g., ud šeš-me dUtu [giš]-Ϟnúϟ-a-gim mu-zi-zi-ia . . . Ϟùϟ tukum-bi dUtu šeš-me

ki kug ki kal-kal-la-aš gù im-ma-an-dé ‘If our brother rises like Utu from bed . . . but

if Utu summons our brother to the holy place’ (Lugalbanda and the Mountain

Cave 123-129). Similarly, when Gilgameš is rendered unconscious by Huwawa’s

auras, his near-death state (sleep being the lesser counterpart of death) is described

metaphorically in terms of sunset (kur ba-an-sùh-sùh gissu ba-an-lá an-usan še-erše-er-bi im-ma-gen ‘the mountains have become indistinct, shadows are cast across

them; the evening twilight has come forth’ [Gilgameš and Huwawa A 78-79]), but

the imagery also, and ultimately, draws upon the notion of the Netherworld as a

place of rejuvenation and rebirth: dUtu úr ama-ni dNin-gal-šè sag íl-la mu-un-gen

‘proudly, Utu has gone to the bosom of Ningal, his mother’ (80).

56

See G. Nagy, Greek Mythology and Poetics (Ithaca, NY/London 1990) 237;

idem, The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry (Baltimore/

London 1999) 196; D. Nakassis, “Gemination at the Horizons: East and West

in the Mythical Geography of Archaic Greek Epic,” Transactions of the American

Philological Association 134 (2004) 215-233.

57

George, Gilgamesh 495. And so Gilgameš’s travel through this mythical space

in a single day mirrors a trip across the expanse of the world, thus underscoring

the theme of coincidentia oppositorum (compare the travels of Odysseus, in which the

extreme west is equated with the extreme east, the island of Aiaie being paradoxically located in both the far west and the far east [see Nagy, Greek Mythology and

Poetics, 237], as well as the travels of Lugalbanda [see n. 68]).

�198

christopher woods

and takes him farther east to the mythical lands beyond. Gilgameš

arrives at Mt. Māšu at night, a fact underscored by his dream and

prayers to Sîn (IX 8-29). The sun has not yet risen over the mountain of sunrise and a new day has not yet begun. The Path of the

Sun, in this scenario, runs through the fantastic lands lying to the

east, between Mt. Māšu and the shore of the cosmic ocean—it is

so designated because these unchartered regions are traversed only

by the Sun-god. Gilgameš crosses this expanse before Šamaš returns

and rises once again over Mt. Māšu, that is, before the dawn of the

following day. Gilgameš and the sun travel in opposite directions,

starting out on their respective ways, likely just as day breaks on

Mt. Māšu. They cross paths at some point late in the race, but

with Gilgameš exiting the eastern end of the Path of the sun, at the

gemstone garden on the shores of the cosmic ocean, before the sun

returns to the western end on Mt. Māšu—[. . . it-t]a- i la-am dŠamši

“[. . . he] came out before the Sun” (IX 170).

One may object that the utter darkness that characterizes the

Path of the Sun is inconsistent with Gilgameš and the sun crossing paths. But, as pointed out by Heimpel, the sun, as it emerges

over the eastern mountains, is described as “flaring up,” i.e., Šamaš

ippu —napā u being a verb commonly used to describe the fanning

of an ember into flame. Conversely, when the sun dips beneath the

mountain of sunset, the verb used is šú ‘to cover’, as in smothering

a flame.58 Thus, during its journey from the mountain of sunset

to the mountain of sunrise the sun was conceived as a smoldering

ember, an understanding that explains why the Netherworld is dark

despite the Sun-god’s nightly travel through it. This rationale also

accounts for the mention of the north wind (IX 163) after nine

double-hours59—the presence of the north wind, which at day break

would re-kindle the sun, being a harbinger of dawn itself—as well

as for Gilgameš repeatedly glancing behind,60 but seeing only darkness61—affirmation that Gilgameš was winning the race, for the sun

had not yet reached Mt. Māšu and erupted into flame.

Heimpel, JCS 38, 142.

Heimpel, JCS 38, 142.

60

ana palāsa arkassa (Gilg. IX 141f.); on the reading palāsa, rather than pānassa,

see George, Gilgamesh 495 n. 176.

61

šá-pak ek-le-tùm-ma i-ba-áš-ši nu-ru “the darkness was dense, and light was there

none” (Gilg. IX 140f.).

58

59

�at the edge of the world

199

A region of darkness beyond the Babylonian oikoumenē is also

known from the Babylonian Map of the World, where a triangular

region, nagû, to the northeast is labeled “Great Wall: 6 leagues in

between where the Sun is not seen.”62 The designation is written

only within this one nagû, but may equally apply to all the nagûs

that radiate from the cosmic sea. A parallel is once again provided

by the Alexander Romance, for, as previously mentioned, the

Macedonian army finds itself in a region of impenetrable darkness in the uncharted regions of India. This is a motif in which

enlightenment and achievement are symbolized by the dawn of a

new day, and ignorance and travail by the preceding darkness of

night—a motif that is captured in a historical omen of Sargon that

reads “. . . the omen of Sargon, who went through the darkness and

a light came out for him.”63 It belongs to the broader symbolism

of the fundamental opposition between night and day, black and

white. That it is an old literary device is shown already by Gudea,

whose revelations come like daylight from the horizon (Cyl. A iv

22; v 19), whose night-time oracular vision (maš-gi6-ka [i 17])—a

play upon ‘black kid’—is obscure, but whose subsequent inspection

of a white kid (máš bar6-bar6-ra), at day break, brings clarity and

a favorable omen (xii 16-17).

More than a mere race to the ends of the earth, Gilgameš’s

contest with the sun has a deeper cosmological significance. And

it is largely a function of two characteristics of the eastern horizon,

which will be discussed further below, namely, that it is here that

time stands still and that fates are determined at dawn, ki dUtu

è ki nam-tar-re-da “the place where the Sun-god rises, the place

where fates are determined.”64 In short, the horizon lies beyond

the Babylonian oikoumenē and, therefore, beyond the laws of nature

that govern the known world. Gilgameš’s quest to circumvent the

ultimate fate of mankind—death—requires him, as a prerequisite,

to traverse the Path of the Sun before his fate is fixed at the dawn

of a new day—a theme that is underscored in the following episode

62

BÀD.GU.LA Ϟ6ϟ bēru ina birit ašar Šamaš lā innammaru (Horowitz, Cosmic

Geography 22: 18; see also ibid., 32-33, where it is noted that ‘Great Wall’ may

refer to mountains).

63

. . . a-mu-ut ϞŠar-ruϟ-ki-in ša ek-le-tam il5-li-ku-ma nu-ru-um ú- i-aš-šu-um (V. Scheil,

RA 27 [1930] 149: text B 16-17—see J. J. Glassner, RA 79 [1985] 124; Horowitz,

Cosmic Geography 33).

64

Steible NBW 2, 343: 7-8; 344: 7-8.

�200

christopher woods

in which Gilgameš must cross the Waters of Death in order to

reach the domain of the immortal Ūta-napišti. By winning the

race, Gilgameš has succeeded in breaking free of the bonds of the

Babylonian oikoumenē; he has bested the sun whose circuit orders

space and regulates time. To transcend the limits of the known

world, delimited by the eastern mountains, is to transcend the very

boundaries of the human condition. It is the prerogative only of

the gods and of mythical figures like Ūta-napišti, immortal, and

Gilgameš, two-thirds divine.

The idea that immortality and rejuvenation are to be sought in

the remote east is, as mentioned at the outset, a theme central to the

Alexander Romance. The east is also where, according to Ctesias,

the mythical dog-headed Kunokephaloi dwell, the longest-lived of

men.65 And it is a conception that is well attested in Mesopotamia

as well, assuming various forms in the literary tradition. The eastern

horizon is the place where the sun is renewed, where the new day is

born, and so—as with the immortal and perpetually young Ushas,

‘Dawn’, in the Rig Veda—it is naturally here that rejuvenation

and longevity are to be found. It is here in the remote, mythical

east, ina rūqi ina pî nārāti “far away, at the Mouth of the Rivers”

(XI 205-206) that the immortal Ūta-napišti is settled and it is here,

within Ūta-napišti’s realm, that Gilgameš must dig a channel to

pluck the plant of rejuvenation, šammu nikitti ‘Plant of Heartbeat’66

(XI 295), which grows deep in the Apsû. Like pî nārāti ‘Mouth of

the Rivers’—the place where the two branches of the primeval river

rise from the Apsû and mingle with the cosmic ocean—the Apsû

itself lies to the east, being physically and, as will become clear in

the following pages, functionally allied to the horizon. 67 Further, it

Romm, Edges of the Earth 80, 82-120.

Following the interpretation of George, Gilgamesh 895-896. Additionally, note

that the black kiškanû-tree of the Apsû, its color a possible signifier of its Netherworld

location, is claimed to have healing, or rejuvenative powers (kiškanû-incantation—see M. J. Geller, “A Middle Assyrian Tablet of Uttukkū Lemnūtu, Tablet 12”,

Iraq 42 [1980] 23-51, idem, Evil Demons 169-171: 95-121; M. W. Green, “Eridu

in Sumerian Literature,” [University of Chicago, Ph.D. 1975] 186-190).

67

In the kiškanû-incantation, Šamaš and Dumuzi are within the Apsû “between

the mouths of the two rivers”—dal-ba-na íd-da ka 2-kám-ma : ina bi-rit ÍD.MEŠ

ki-lal-la-an (M. J. Geller, Iraq 42 [1980] 28: 16', 18'; idem, Evil Demons 170: 102);

see also n. 84 below. As for the easterly location of the Apsû, note that the term

for Utu’s cella, agrun (kummu), is nearly identical with the Abzu and that it is in

the Abzu that Utu meets Enki: èš Abzu ki-zu ki-gal-zu ki dUtu-ra gù-dé-za “the

shrine Abzu is your [i.e., Enki’s] place, your Netherworld; it is the place where

you greet Utu (Temple Hymns 17: 15-16). Steinkeller has connected this passage

65

66

�at the edge of the world

201

is here, at the eastern limit of his journey, that Gilgameš is cleansed

and refreshed, where Ūta-napišti gives him a robe for his return

journey that promises to be perpetually new, a taunting symbol of

the immortality of the eastern horizon that has eluded him.

These aspects of the east are well known in Sumerian literature

as well, for it cannot be coincidental that it is in the distant, eastern mountains that an exhausted Lugalbanda, near death, finds

renewed strength—indeed, he attains super-human speed, a veritable rebirth.68 And a frustrated Gilgameš, realizing the inevitability

of death and resolving to establish his everlasting renown in lieu of

immortality, endeavors to do so in the east, searching for Huwawa in

lands under the sway of Utu, journeying to kur-lú-tìl-la—“mountain

where one lives”69—a reference either to Ziusudra,70 specifically,

or, more likely and more profoundly, to the belief that immortality

is to be found on the eastern horizon, so introducing the mortality

theme that pervades the story and dominates the following speech

to Utu (ll. 21-33) in particular. Finally, agreeing in the essentials

with the later Akkadian epic, there is this account in the Sumerian

Flood Story: An and Enlil, having decreed immortality for Ziusudra,

with two Sargonic seals (Boehmer, Entwicklung Abb. 488 and 489), which depict

Utu before Enki, who is portrayed within his watery shrine (Steinkeller, Quaderni

di Semitistica 18, 258 n. 39). This conception is confirmed for the late periods by

a NB ritual that identifies Šamaš as mud-an-na-[x] bí-[h]a-za-e-eš GIŠ.NÁ-an-na

bí-tab : mu-kil [up]-Ϟpiϟ Ap-si-i ta-me-e nam-za-qí šá dA-ni7 “(Šamaš) who holds the

lock of the Apsû, who keeps the key of Anu” (UVB 15, 36: 12; following CAD N/1

sub namzaqu lex.). As discussed below, further support is to be found in the notion

that stars originated in the Apsû—see R. Caplice, “É.NUN in Mesopotamian

Literature”, Or 42 (1973) 299-305.

68

Lugalbanda’s gift of super-human speed, bestowed by Anzu on Mt Hašur,

allows him run as fast as the sun and the celestial sphere (ud-gim du dInana-gim

ud 7-e ud dIškur-ra-gim izi-gim ga-íl nim-gim ga-gír ‘Travelling like the sun, like

Inana, like the seven storms of Iškur, may I leap like a flame, may I blaze like

lightining!’ [Lugalbanda 171-173; cf. 188-190]), and so he is able to cross seven

mountain ranges and return to Uruk from Anšan in a single day, “by midnight,

before the offering table of holy Inana was brought out” (gi6 sa9-a gišbanšur kug

d

Inana-ke4 nu-um-ma-tèg-a-aš [Lugalbanda 345]); cf. Gilgameš’s race against

the sun and the travels of Odysseus (see n. 57). Similarly, in Lugalbanda and the

Mountain Cave, the hero’s rejuvenation is realized once he consumes the Plant

of Life (ú nam-tìl-la-ka; cf. šammu nikitti ‘Plant of Heartbeat’ [Gilg. XI 295]) and

Water of Life (a nam-tìl-la-ka), which are found on Mt. Hašur, enabling him to

race over the hills like a wild ass, from nightfall until the coming of the following

evening (ll. 264-277).

69

Gilgameš and Huwawa A 1. For a differing opinion with previous literature

on this passage, see G. Steiner, “ uwawa und sein ‘Bergland’ in der sumerischen

Tradition”, ASJ 18 (1996) 187-215.

70

For this interpretation, see George, Gilgamesh 97-98, with previous literature.

�202

christopher woods

“settle him in an overseas country, in the land of Tilmun, where

the sun rises.”71

Much has been made of Tilmun in the Sumerian Flood Story,

particularly in light of the island’s role in Enki and Ninhursag.

But I suggest that Tilmun’s mythological status—with regard to

Ziusudra and immortality at least—has less to do with the inherent

qualities of the island, or with any notion of a Sumerian paradise,

than with the simple fact that Bahrain lies in the remote east. At

the likely time of the Flood Story’s composition, the Ur III or OB

period, Tilmun was, by virtue of its trade, a location of considerable prominence on the Mesopotamian mental map and thereby

served as a magnet, attracting to itself the mythological notions

of the east. Much like the vague and mystical notions that surrounded Aratta, another place identified with the far east, Tilmun

was a convenient toponym that gave shape to the vague notions of

cosmography, the peg of reality on which the abstract was hung.72

It is an interpretation that is again suggested by the version of the

Flood presented in Gilgameš—a tale concerned more with cosmic

geography and written in an age when Tilmun’s importance had

waned—in which there is no mention of Tilmun, and Ūta-napišti,

the “Far-Away,” resides at the mythical pî nārāti “Mouth of the

Rivers.” No doubt the unexpected fresh water springs of Tilmun

contributed to its resemblance to the cosmic pî nārāti, evoking, as

George has discussed, the late understanding of classical and Arabic

sources that the Tigris and Euphrates resurfaced on the island.73 But,

again, the mythologization of Tilmun in this regard—its association

with immortality—likely grew out of the broader mythology of the

east, Tilmun becoming a real world incarnation of the vague and

indefinite. As we shall see, rivers were integral to the cosmic geography of the east, appearing in contexts having nothing to do with

the destination of the Tigris and Euprates, nor with pî nārāti.74

71

kur-bal kur-dilmun-na ki-dUtu-è-šè mu-un-tìl-eš (The Flood Story, Segment

E 11).

72

Arguing on different grounds, P. Michalowski reaches a similar conclusion:

“Dilmun, which in certain contexts undoubtedly has a real referent, has to be

considered as a mental construct in literary texts, a name without any necessary

connection with the topography of a particular place” (“Mental Maps and Ideology:

Reflections on Subartu”, in: H. Weiss, The Origins of Cities in Dry-Farming Syria and

Mesopotamia in the Thrid Millennium B.C. [Guilford, CT 1986] 134-135).

73

George, Gilgamesh 520.

74

Further, in the tradition that is preserved, the Tigris and Euphrates were

conceived as flowing to the mythical Mt. Hašur, and not Tilmun: A.MEŠ ídHAL.

�at the edge of the world

203

Creation and the Space-Time Metaphor

No feature of the horizon better reflects the mythology of the

east than the cosmic Du6-kug, the Sacred Mound, source of all

things. Like Mt. Māšu, which extends from the Upperworld to

the Underworld, from šupuk šamê ‘the firmament’ to arallû ‘the

Netherworld’, Dukug bonds heaven with earth.75 Indeed, Dukug,

specified as the place where fates are determined, is synonymous

with the mountain of sunrise in some contexts: “Šamaš, when

you emerge from the great mountain, when you emerge from

the great mountain, the mountain of springs, when you emerge

from the Sacred Mound, where destinies are decreed . . .”76 This is

a cosmological notion for which there is a cultic counterpart, for

the temple, conceived as a microcosm of the cosmos—the universe

in miniature—contained a Dukug as a cultic installation, a raised

platform on which fates were fixed. Thus, of the Eninnu it is said:

sig4 Du6-kug-ta nam-tar-re-da “brickwork, on (its) Sacred Mound

destiny is determined,”77 while in Babylon the Dukug was known

as parak šīmti “Dais of Destinies”—“the Sacred Mound, where destinies are decreed.”78 As expressed by an epithet of Eunir, Enki’s

temple in Eridu, Dukug is further recognized for its ambrosia-like

sustenance: Du6-kug ú sikil-la rig7-ga “Sacred Mound where pure

food is consumed,”79 a notion that draws from a broader conception of the eastern horizon as a place of abundance and plenty

beyond the ordinary. In the Death of Ur-Namma, Inana cries that

failure to observe the divine ordinances (giš-hur) will result in “no

HAL A.MEŠ ídPu-rat-ti KUG.MEŠ šá iš-tu kup-pi a-na kur a-šur a- u-ni “Pure waters

of the Tigris and the Euphrates, which come forth from (their) springs to Mt.

Hašur” (KAR 34: 14-15)—see W. F. Albright, “The Mouth of the Rivers”, AJSL

35 (1919) 176-77; George, Gilgamesh 864.

75

Gilgameš IX 40-41; cf. hur-sag an-ki-bi-da-ke4 ‘upon the hill (lit. mountain

range) of heaven and earth’ (Lahar and Ašnan 1). Horowitz, Cosmic Geography 98,

notes that Mt. Simirriya in Sargon’s 8th campaign (TCL 3 i 18-19) is described

in similar terms. That mountains were envisioned as reaching down to the

Netherworld likely contributed to kur as a designation for the latter.

76

R. Borger, JCS 21 (1967) 2-3: 1-3 (bīt rimki ).

77

Temple Hymns 31: 245.

78

[D]u6-k[ug] ki nam-tar-tar-re-Ϟeϟ-[dè] : [MIN dLugal-dìm-me-er-an-ki-a šá

ub-šu-ukkin-na . . .] “Du-kug Ki-namtartarede (“Pure Mound, where destinies

are decreed”) [the seat of Lugaldimmerankia in Ubšu-ukinna . . .]” (George,

Topographical Texts 52-53: TINTIR II: 17'; see the comm. on pp. 286-287, 290291, with further evidence for Dukug as a cultic installation in various cities).

79

Temple Hymns 17: 4.

�204

christopher woods

abundance at the gods’ place of sunrise,”80 and in Gilgameš and the

Bull of Heaven, An informs Inana that the Bull of Heaven, Utu’s

alterego, “can only graze at the place where the sun rises.”81 Like

the gold and pearls that pave the paths of the Land of Darkness in

the Greek Alexander Romance (II.40-41), this is a notion that in

Gilgameš takes the form of the mythical garden of gemstones at the

eastern end of the Path of the Sun, on the shores of the cosmic sea.82

More than a place of supernatural abundance, however, Dukug, in

Lahar and Ašnan, is the primeval location of the Creation: this is

the place where An spawned the Anuna gods, where the gods dwell,

the place where sheep and grain, the basis of civilization, were first

created.83 Dukug as kur idim/šad nagbi “mountain of springs,” and

so perhaps to be identified with pî nārāti “Mouth of the Rivers,” is

also the place from where the headwaters of the cosmic river rise

from the Apsû—this is Íd-mah ‘Great River’, the primeval river,

which in other contexts carries the epithet bānât kalama “creatrix

of everything.”84

giš-hur kalam-ma hé-me-a-gub-ba sag ba-Ϟra-ba-anϟ-ús-sa ki ud è dingir-ree-ne-šè nam-hé-gál?-Ϟbiϟ nu-gál “if there are divine ordinances imposed on the

land, but they are not observed, there will be no abundance at the gods’s place

of sunrise” (Death of Ur-Namma 210-211).

81

lú-tur-mu gud an-na ú-gu7-bi in-nu an-úr-ra ú gu7-bi-im ki-sikil dInana gud

an-na ki dUtu è-a-šè ú im-da-gu7-e za-e gud an-na nu-mu-e-da-ab-zé-èg-en “My

child, the Bull of Heaven would not have any pasture, as its pasture is on the

horizon. Maiden Inana, the Bull of Heaven can only graze where the sun rises.

So I cannot give the Bull of Heaven to you!” (Gilgameš and the Bull of Heaven,

Segment B 47-49).

82

Horowitz, Cosmic Geography 102 already points out the parallel with the

Alexander Romance, and further parallels are discussed by George, Gilgamesh

497-498 and nn. 185-186.

83

Lahar and Ašnan 2, 26-27.

84

Íd-mah is here considered to be a manifestation of dÍd (also Woods, ZA 95

[2005] 7-45); that this river flows on the eastern horizon is shown by Ibbi-Sîn

B, Segment A 23-24, discussed below (see n. 154). For the epithet bānât kalāma/u

“creatrix of everything,” see the Incantation to the River (R. Caplice, Or 36 [1967]

4: 6; STC 1, 200: 1, 201: 1; ed. pp. 128-129). The notion that kur idim/šad nagbi

“the mountain of springs,” i.e., Dukug, is to be identified with the mountain of

sunrise—and, moreover, that the waters springing forth ultimately derive from

the Apsû—is made explicit in the following: a i-di-im sikil-la-ta Eriduki-ta mú-a :

A.MEŠ nag-be KUG.MEŠ šá ina E-ri-du ib-ba-nu-ú, kur i-di-im sikil-la-ta kur erenna-ta im-ta-è : ina KUR-e nag-be el-li KUR e-re-ni ú- u-ni “pure water of the spring,

which originated in Eridu (i.e., the Apsû), and has flowed forth from the mountain

of the pure spring, the mountain of cedars” (STT 197 rev. 57-60; ed. J. S. Cooper,

ZA 62 [1972] 74: 28-29; šad erēni, as noted above, is one of the epithets of the

mountain of sunrise). Further evidence for spring(s), nagbu, issuing forth from the

Apsû appears in the bilingual excerpt: idim-Abzu-ta agrun-ta è-a-meš : ina na-gab

80

�at the edge of the world

205

The eastern horizon as the setting of creation is a conception that

finds an intriguing counterpart in Enki and Ninhursag, a creation

myth set in distant Tilmun. What this myth describes at the outset

(11-28)—and what is also described in the incantation recited in

Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta (136f.) and, apparently, reiterated

in a fragmentary literary text from Ur (UET 6, 61)—is a period of

pristine primitivism at the Beginning, a period without the benefits

of civilization, but also without the negative implications apparently

associated with it: free of disease, death, predation, or fear, a time,

as related in Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta (146), before the

confusion of tongues.85 This is a period of stasis with time at a virtual

standstill: “No old woman said: ‘I am an old woman’. No old man

said: ‘I am an old man’.”86 From this point of timelessness, time

begins to unfold, as gauged by mortal longevity, but at an imperceptibly slow pace, gradually quickening during the mythical past

until it reaches its familiar stride. It is a notion that is also found

in the Sumerian King List, where the antediluvian rulers reigned

for tens of thousands of years, their postdiluvian counterparts thousands and hundreds of years, with the length of reigns gradually

diminishing to mortal levels. And it holds true for the Early Rulers

of Lagaš, according to which a postdiluvian childhood lasted one

hundred years and adulthood another one hundred years, while the

Ap-si-i ina ku-um-me ir-bu-u-šú-nu “they grew up in the spring(s) of the Apsû, in the

cella” (CT 16, 15 v 34-36; cf. ibid. 30f.; CT 17, 13: 14; 4R 2 v 32-33—see CAD

N/1 sub nagbu A lex.), while the bond between Dukug and Apsû is demonstrated

by the fact that Dukug may serve as a byname for the latter (Du6-kug : Ap-su-u

[Malku I 290]; cf. [du-ú] : DU6 = šá Du6-kug Abzu [Idu II 33]; cf. Temple Hymns

17: 3-4). Collectively, the evidence suggests an identification, or at least a close

association, of pî nārāti with Dukug.

85

On this point see already Alster, BBVO 2, 56-58; T. Jacobsen, “The Eridu

Genesis”, JBL 100 (1981) 516, with the relevant lines of UET 6, 61 (identified

by Jacobsen as a version of the Flood Story) given in 516-517 n. 7. P. Attinger

(“Enki et Nn ursa‘ga”, ZA 74 [1984] 33-34) and most recently D. Katz (“Enki

and Ninhursa‘ga, Part One: The Story of Dilmun”, BiOr 64 [2007] 578), among

others, maintain a very different interpretation of this passage; I will discuss these

issues further in a forthcoming study of the grammar and context of Enki and

Ninhursag 1-3.

86

um-ma-bi um-ma-me-en nu-mu-ni-bé ab-ba-bi ab-ba-me-en nu-mu-ni-bé

(Enki and Ninhursag 22-23). Of course, the notion that antediluvian man enjoyed

life without limit is central to Atrahasis; the theme is also found in the description of primordial times in Lugalbanda and the Mountain Cave, i.e., [ud ul an

ki-ta bad-rá-a-ba] . . . sag gi6 zid sù-ud-Ϟbaϟ mi-ni-ib-dùg-ge-eš-ba ‘When in ancient

days heaven was separated from earth . . . when the black headed (people) enjoyed

long life’ (1, 15).

�206

christopher woods

reigns of the earliest rulers lasted thousands of years beyond that,

but during that time the essential technologies of civilization—the

hoe, the plow, irrigation—did not yet exist. As described in Lahar

and Ašnan, this was a period of complete primitive simplicity in

which “the people of those days did not know about eating bread.

They did not know about wearing clothes; they went about the

land with naked limbs. Like sheep they ate grass with their mouths

and drank water from ditches.”87

What is described here is a stark-primitive ideal that is associated

with a purity, a longevity, and, as will be described in the following

pages, a wisdom, that is beyond contemporary mortal bounds. As

raw and vulgar as Lahar and Ašnan portrays this inchoate state,

the evidence taken as a whole describes a Golden Age of sorts,

granted one having nothing to do with a Sumerian paradise, but

a Golden Age nonetheless from which man has steadily declined,

civilization coming at the cost of purity88—a motif for which crosscultural parallels can be drawn from Hesiod’s vanished ages, to the

Taoist age of sage-kings, to the notions of the Noble Savage during

the Enlightenment. However, it is the Tilmun setting of Enki and

Ninhursag that is of particular interest to this discussion. Clearly,

the myth is in part an etiology for Bahrain’s defining characteristics,

explaining its unexpected fresh-water springs, its Enki cult, and its

prosperous trade. Yet, like Ziusudra’s connection with the island, it is

the broader mythology of the east that allows Tilmun as the setting

of the inchoate world to be conceptually feasible. Essentially, what

is at issue is a coupling of the iconic structures of space and time,

a metaphorical relationship in which distance in space is equated

with distance in time, creating an opposition here, now vs. there, then.

By this same rationale, longevity and rejuvenation are placed in

the contexts of both the distant past and the remote east—just as

the immortal Ziusudra and his Babylonian counterpart Ūta-napišti

dwell on the eastern margin of the map, and as Lugalbanda finds

rejuvenation in the eastern mountains, so mankind in ages past

lived lives of Methuselian lengths. And this same relation holds

87

ninda gu7-ù-bi nu-mu-un-zu-uš-àm túg-ga mu4-mu4-bi nu-mu-un-zu-uš-àm

kalam giš-ge-na su-bi mu-un-gen udu-gim ka-ba ú mu-ni-ib-gu7 a mú-sar-ra-ka

i-im-na8-na8-ne (Lahar and Ašnan 21-25).

88

Cf. Alster, BBVO 2, 55-58, who in his efforts to debunk the myth of a

Sumerian paradise—and he is no doubt correct on that point—goes further;

seeing only the negative aspects of this primeval state, Alster describes it as “pure

barbarism” (ibid., 57).

�at the edge of the world

207

with respect to simplicity and primitivism and the far east, for the

eastward travels of Gilgameš and Lugalbanda through the wilderness amount to a return to primordial times, when man was like

the beasts and civilization did not yet exist.89

It is the identity of distance in space and distance in time that

accounts for the Mesopotamian belief that fates were determined

both at the Beginning and, in mimicry of the event, each day at ki

d

Utu è-a “the place where the sun rises.” As the cosmos began in

the primordial past, each day begins in the remote east, ‘distance’

being the coordinate common to both. And such is the rationale for

the primeval past and the eastern horizon sharing a set of literary

images. In Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, the idyllic Golden

Age, devoid of fear and predation, is first described as ud-ba muš

nu-gál-àm gíri nu-gál-àm “a time without snakes and without scorpions” (136) and this description is apparently repeated verbatim in

UET 6, 61, which may be related to the Flood Story.90 Remarkably,

this same imagery describes Mt. Hašur, the mountain of sunrise, in

Lugalbanda: da-da-ba ha-šu-úr nu-zu kur-ra-ka muš nu-un-sul-sul

gíri nu-sa-sa . . . “Nearby, upon Mt. Hašur, the unknowable mountain, where no snake slithers, no scorpion scurries . . .” (36-37).

The loss of immortality, the great longevity of antediluvian

man, and his decline with successive generations, naturally evokes

Genesis,91 but it is Hesiod who provides the more compelling parallel, capturing not only the temporal, but also the spatial dimensions

of the Golden Age, for the survivors of the fourth generation of

man live apart from other men, dwelling “at the ends of earth. And

they live untouched by sorrow in the islands of the blessed along

the shore of deep-swirling Ocean.”92 Like most cultures, the Greeks

had an ethnocentric view of the world, one in which Greece was

Lugalbanda is reduced to foraging like a wild animal (zag-še-gá ki um-mani-ús a kušummud-gim ù-mu-nag ur-bar-ra-gim gúm-ga-àm mi-ni-za ú-sal ì-kú-en

tu-gur4mušen-gim ki im-de5-de5-ge-en i-li-a-nu-um kur-ra ì-kú-[en] ‘Lying on my side,

I drank water as from a water-skin; I howled like a wolf, I grazed the meadows;

I pecked the ground like a pigeon; I ate the mountain acorns’ [Lugalbanda 241243]), and must re-learn and re-create essential elements of civilization, such as

making fire from flint and baking bread (Lugalbanda and the Mountain Cave

287-293). Gilgamesh, in his wanderings east towards the realm of Ūta-napišti,

slaughters lions for food, clads himself in their skins, and digs wells that did not

exist previously (Gilg. OB VA+BM i 1'-3').

90

Jacobsen, JBL 100, 517 n. 7: 11'; also Alster, BBVO 2, 56-58.

91